Part 1: Foundations of Data Systems

Ch. 1: Reliable, Scalable and Maintainable Applications

- Most applications are data-intensive rather than compute-intensive. This means that compute does not limit apps, it’s the ability to handle data

- Built on common building blocks: databases, caches, search indexes, stream and batch processing. The way of doing these building blocks are different

- Use application code to stitch all of this together rather than implementing each

- Most important concerns for software systems:

- Reliability: system should continue to work correctly even if facing adversity (faults)

- Scalability: system should be able to deal with growth

- Maintainability: system should be easily maintainable as it grows

- Application must meet:

- Functional requirements (what it should do)

- Non-functional requirements (general things like security, reliability, compatibility)

Reliability

- Systems that can anticipate and cope with faults (breaks in system) are fault-tolerant

- Not tolerant of all errors, just certain ones.

- Faults are not failures. Faults are when things deviate from spec, while failures are when the system stops providing to the user. Preventing faults is harder than tolerating them

- Sometimes, we deliberately initiate faults in system to clear bugs and test fault tolerance

- Hardware faults: disks crash, RAM doesn’t work, power outage

- Use redundancy: have several disks in place, dual power supplies, hot-swappable CPUs, backup power

- Sometimes need software tolerance software to tackle entire machines that are faulty. Allows for rolling upgrades (eg. each node in cluster updated)

- Software faults: bugs, runaway processes, corrupted responses, cascading failures

- Usually software faults are dormant until triggered by weird circumstances

- Much harder to avoid. Rigorous testing, logging and alerting needed

- Human faults: human faults are usually much more common than hardware faults

- Prevent through documentation, well-designed APIs, create sandbox envs that mimic prod, test, use roll backs in Git, set up monitoring to catch, training

- Reliability is important because if software goes down, we lose productivity and not very responsible to end users. Be careful cutting corners

Scalability

- All about coping with increased load

- Load can be described in several different ways: requests/second, read:write ratio, concurrent users, cache hit rates. Known as load parameters as load is a function of these

- Ex: Twitter has two primary functions: posting (4.6-12k requests/sec) and timelines (300k requests/sec)

- The challenging part is not tweet volume, but fan-out: one user follows multiple people and followed by multiple people

- Could either insert new tweet and merge into follower timelines in a relational DB or maintain a cache for a user’s timeline and insert into cache

- 1st version struggled to cope with load, so switched to second. However, second one has a lot of writes (especially with people that have millions of followers). Now they are merging the two versions so that people with large fanbases are using the relational DB version

- Load parameter: followers/user. Key mover to scalability for Twitter

- Can look at load by increasing load parameters and seeing how performance is affected if no new resources added or how much you would need to increase resources for unaffected performance

- How to measure performance: throughput (amount/time) or response time (time/action)

- Latency is not response time. Latency is how much time it takes for request to wait before handling. Response time is the time it takes for the client to see (including latency)

- Think about these numbers using distributions. Percentiles typically better to measure top, middle or low-end of performance. Tail percentiles are important

- Percentiles are often used in service level agreements (contract that define expected performance and availability of service)

- Queuing delays account for abnormal delays as CPUs can only handle so many tasks in parallel. If one task held up, it will slow everything down

- How to cope with load: will need to rearchitect every single time your load 10x

- Can either scale up (vertical scaling, move to a more powerful machine) or scale out (horizontal scaling, use multiple weaker machines)

- Usually, you will need to scale out. Higher end machines typically are expensive

- Can scale manually or programmatically (known as elastic service). Manual scaling is simple, but dynamic scaling is useful for unpredicatable loads

- Each service needs different scaling architectures due to different needs. Often done while keeping in mind which operations are common and which are rare

Maintainability

- The cost in developing software is not the initial development but the maintenance

- We need to design software such that it will minimize maintenance pain and avoid creating legacy software (lots of mistakes, outdated, systems were built to do things they weren’t supposed to do)

- Design principles for software systems involving maintainability:

- Operability: make it easy for operations teams to keep system running smoothly

- Simplicity: new engineers should easily understand system, remove as much complexity

- Evolvability: make it easy for engineers to change system in the future

- Operability:

- Operations can be automated, but its up to humans to set up automation and make sure its working correctly

- Operations teams responsible for: monitoring health, root cause analysis, keeping software up to date, system integration, antcipating and solving future problems, deployment, maintenance, security

- Data systems can: provide good monitoring, provide support for automation and integration, avoid dependencies on machines, docs, admin overrides, self-healing, predicatable behaviour

- Simplicity:

- Complex software is really difficult to work with

- Use abstractions to provide clean and standard interfaces to reduce complexity

- Evolvability:

- Requirements change, so you need to easily change software to meet criteria

Ch. 2: Data Models and Query Languages

- Data models are our representations of different parts of the software stack, so it is very important

- Software has several layers. Each layer needs to hide details and complexity by providing data models (eg. Python programmers don’t really need to care about computer hardware optimizations)

Relational model vs. document model:

- Relational: data organized in relations (known as tables in SQL) where each relation is an unordered collection of tuples (rows in SQL). Quite clean

- NoSQL started in 2010s. Why?

- Need for greater scalability is pretty easy using NoSQL

- Everyone likes open-source software over commercial databases (usually relational)

- Some queries don’t work great on relational model

- Relational models are restrictive (for a good reason)

- We will most likely have polyglot persistence: both SQL and NoSQL used for data

- A lot of programming is done in object-oriented languages which doesn’t map really well to tables. Need ORMs (object-relational mappings) to reduce amount of work

- Simple example: the resume. First and last name are used once/resume so they can be in columns. What about experience/extracurriculars? 1 resume → many experiences!

- Supporting 1:many: have different tables for experiences and use foreign keys, store structured datatypes/XML, or encode as JSON and store as string (which many prefer)

- JSON way of doing 1:many is pretty clean (everything all in one table, no joins needed. Known as locality)

- Why do we use IDs for things that are human readable, like geography? We can use IDs to define a standard, easier to localize to different languages, easy to update.

- Also prevents duplication: we would otherwise repeat human info throughout records rather than just a simple ID. These human info are likely to change so updating would be a pain

- This is known as normalization: reduce the amount of redudancy in a database

- Issue: many-to-one relations needed **(**many people in one region, many people in one industry), which isn’t great for document JSON model. Wouldn’t joins make things simple? NO! JSON joins are really tough and you will need to do it yourself

- Another issue: these many-to-one relations often have more and more info added, so joins get even MORE painful

- Another issue: many-to-many joins are an absolute pain

- Network model: basically think of it like a graph

- Issue: querying would require traversals, which can be really expensive for large graphs

- Relational models are easy because joins are done automatically because it’s all just based on index matching and it’s pretty easy to optimize (just need to do it once and ALL queries benefit)

- Document models are now using document references for foreign references

- Why document model? Super flexibile, better performance due to locality, mimics data structures

- Why relational model? Better join support and can easily support many-to-one and many-to-many

- Which leads to simpler code?

- Depends on structure: if application data is tree-like, document model might be better. If you shred a relational database (have several tables for one-to-many support), you can make things very complicated. If lots of relationships, then the network model might be best

- If things are too nested in a document, the code can get complex quick

- Many-to-many is 10x simpler in relational model

- You could technically denormalize (have redundant data) but then you need to make sure all the redundant data is consistent

- Document databases don’t enforce schemas as strictly and really only care about implicit schemas on reads (not writes like SQL)

- If you want to change the structure of the data, you would need to perform migrations for SQL databases. Document databases allow immediate change, but you just need to handle the case where you read old data

- Schemas are useful to enforce structure, but not always needed

- Locality in document databases are nice because it is much more performant: you don’t need to join a lot of tables to get your information

- Really only advantageous if documents are small and you use majority of data. Otherwise, you are loading a lot of info you don’t need

- Relational models also have ability (especially columnar ones), but a little clunky

- A lot of relational databases support JSON columns and non-relational getting better with joins

Query Languages for Data

- SQL is declarative: you specify patterns and conditions, but you don’t tell exactly how to perform querying (relational algebra)

- This is nice because concise, hides details so that database can optimize without changing queries, and can be parallelized because no algorithm is set by user

- CSS is declarative as well!

- MapReduce: uses mapping and reducing paradigm in functional programming to handle queries on big data in a distributed fashion

- Some SQL databases support MapReduce querying

- MongoDB has aggregation pipelines (kinda like MapReduce)

Graph-like Data Models

- Remember: graphs are really good when you have data with lots of relations (eg. social graphs, web graphs, traffic)

- For each node and edge, you can have different types of data as well

- Eg: Facebook uses people, locations and events as different nodes, while comments, likes and friends (all different entities) are edges

- Property graph model:

- Vertex has UUID, set of outgoing and ingoing edges and properties. Edges have UUID, start and end nodes, labels and properties

- No restriction on what you can connect, pretty easy to traverse, can store different types of information

- Graphs are pretty easy to extend and evolve

- Cypher: query language for graphs (specifically Neo4j). Declarative, so you don’t need to do the execution and optimizer chooses best strategy

- You can do this in SQL, but lots of joins needed (especially need to know in advance)

- Variable length traversals in a graph are not handled well in SQL

- Triple-store graph model:

- Everything in three-part statements: a subject, predicate and an object

- Subject is a node in the graph. The object can be a value (so predicate and object are key:value pairs) or another node

- Somewhat inspired semantic web (web published in machine readable format that can be easily converted to a graph)

- Query language: SPARQL

- Datalog was the original query language for graphs (subset of Prolog)

Ch. 3: Storage and Retrieval

- Most databases use a log where you add something to the end of the file efficiently

- To retrieve data efficiently, you will need to use an index. Speeds up read time but slows down writes

- Up to the developer to choose right index to make sure tradeoff isn’t too bad

- Simplest: use a hashmap that maps index to value (although hashmap must fit in memory), segment logs into different files to prevent storage issues, and compaction to prevent duplicate entries

- Storage engine needs to check hashmap of most recently modified segment for data, then moves to next, then moves to next…

- Issues: CSV isn’t great for logs (raw binary is better), deletion requires a flag to indicate deletion so segment merging can remove it, some way to store hash maps if DB crashes, need checksums to make sure data isn’t corrupted, concurrency not really supported (only one writer thread, multiple read threads), range queries are inefficient

- Sorted string table (SSTable): upon insertion into segment file, make sure keys are sorted

- Much easier to merge different segments because they are sorted by key and only keep the record that was most recent if multiple keys with same value

- Also much easier to find index keys because sorted, so we only need to keep some offsets in memory rather than entire hash map

- Can compress set number of values from offset to offset, saving space

- Implementation: use balanced tree structure (AVL or red-black trees) known as memtable, write to file and start new memtable when too big and run compaction and merging in background

- Issue: if crashes, in memory memtable lost. Can keep separate unsorted log that can restore memtable in crash and discarded everytime tree instance is done

- Can have multiple SSTables in log-structured merge-tree (LSM-Tree)

- Lucene (powers Solr and Elasticsearch) uses this method with the key being words and the value being IDs to documents

- Optimizations: use Bloom filters to check if index is even in DB without needing to check all trees and segments, compaction strategies (size tier: merge smaller SSTables into bigger tables. levelled: use key ranges

- Pretty efficient with range queries, can support high write throughput

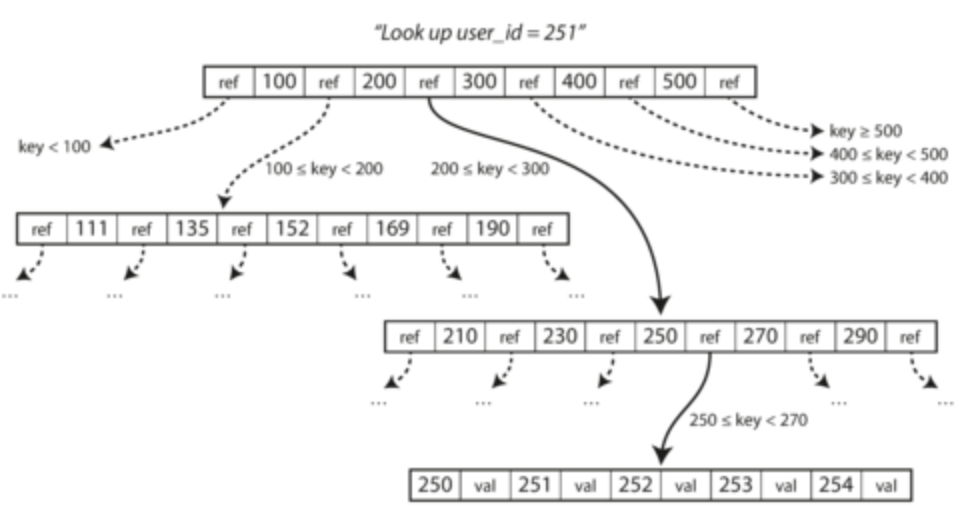

- B-tree: pretty much the standard implementation

- Rather than breaking logs into segments (usually several megabytes) and then creating key value pairs, B-trees break database into blocks/pages (4 KB) and read/write one page at a time

- Pages can be identified via address like pointers (but on disk, not in memory)

- Pages have references to child pages. The number of child refs is called the branching factor

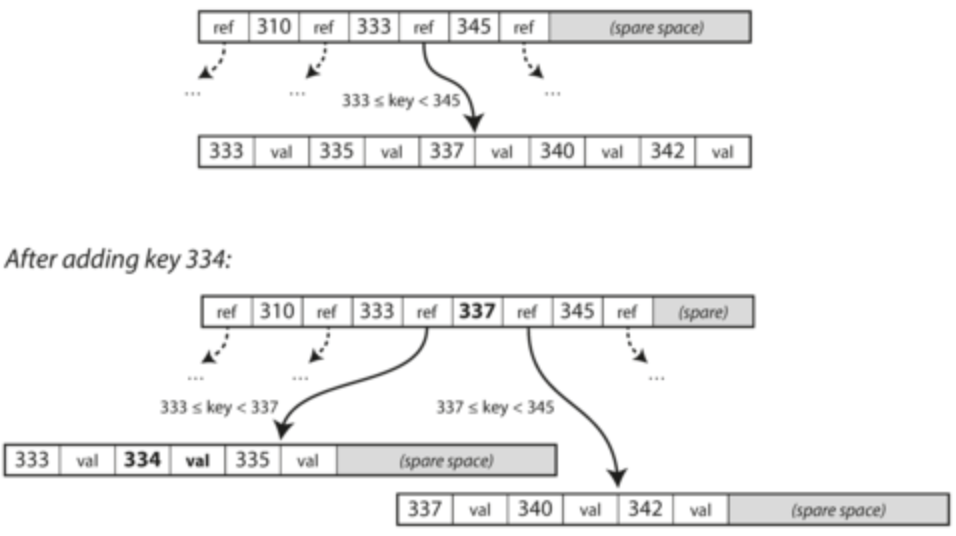

- If you want to add/edit a key, use child pages to get to right range and add new key. If page is too small, split page into two and update parent

- This algo ensures B-trees remain balanced and have O(log n) depth. Most DB can fit into B tree with a pretty small number of levels (4 levels)

- Important: B-trees overwrite data rather than appending new data like LSM-tres, which makes it vulnerable to crashes

- To make it more resilient, B-trees often have write-ahead logs where every modification must be written to append-only file, which can be used to restore tree

- Also needs to implement latches so proper concurrency without inconsistent data

- Optimizations:

- Rather than rewrite, copy-on-write and update references

- Put key limits, especially in inner parts of the tree

- Can optimize location of pages so all leafs in one section

- More pointers to sibling pages

- B-trees better for reads, LSM-trees better for writes

- Beware of write amplification: writing one record will lead to multiple writes on disk over time because of redundancies. This is problematic for SSDs which wear out

- LSM-trees have better compression than B-trees

- LSM-tree compaction can impact write and read performance (especially for p95), might not handle high write throughput (could have lots of compaction happening)

- Secondary indices: create another column as a secondary key, very useful for making joins even more performant. Need to do a little bit of modification to make sure indices are unique

- Values can refer to heap file instead of storing the value on the same page. This enables multiple rows to use same data but data only stored once. Pretty efficient

- If this is too slow for reads, you can use clustered index by storing the row within the index

- Can also just store a few columns in the index, known as a covering index because it covers some queries

- Multi-column indices: can combine multiple columns by concatenating to form index or other methods. Especially useful for geospatial data

- Can use LSM-tree approach to support fuzzy searching as well

- We like to use disks over RAM because disks are durable (disks also used to be cheaper/GB, but RAM is getting cheaper). Some DBs are completely in-memory (RAM)

- Example: Memcached.

- Can write to disk still, but all reads served from RAM and written data is used to boot up in-memory DB

- In-memory has performance improvements because it doesn’t need to care about encoding data structures such that it is written on a file

- Because of this, in-memory DBs like Redis can use data structures like priority queues and sets which are hard to do on disk.

- Anti-caching approach: use in-memory and evict LRU memory to disk if capacity reached, but pull back when capacity available

Transaction Processing or Analytics

- Transactions: group of low-latency reads and writes (opposed to batch processing)

- Process of updating and deleting in transactions is known as online transaction processing (OLTP)

- Analytics is pretty different: need to scan over a large numebr of records and calculate aggregate statistics

- Process known as online analytics processing (OLAP)

- Many engineers do not want analytics queries run on OLTP systems, because actual users are using it. Want as high availability as possible

- Solution: put a copy of the data in a data warehouse. Usually read-only data and extracted from OLTP periodically or streamed via ETL pipelines (extract-transform-load)

- Big advantage: OLTP optimized for transactions, warehouses optimized for OLAP

- Optimizations include Hadoop-based systems, AWS Redshift

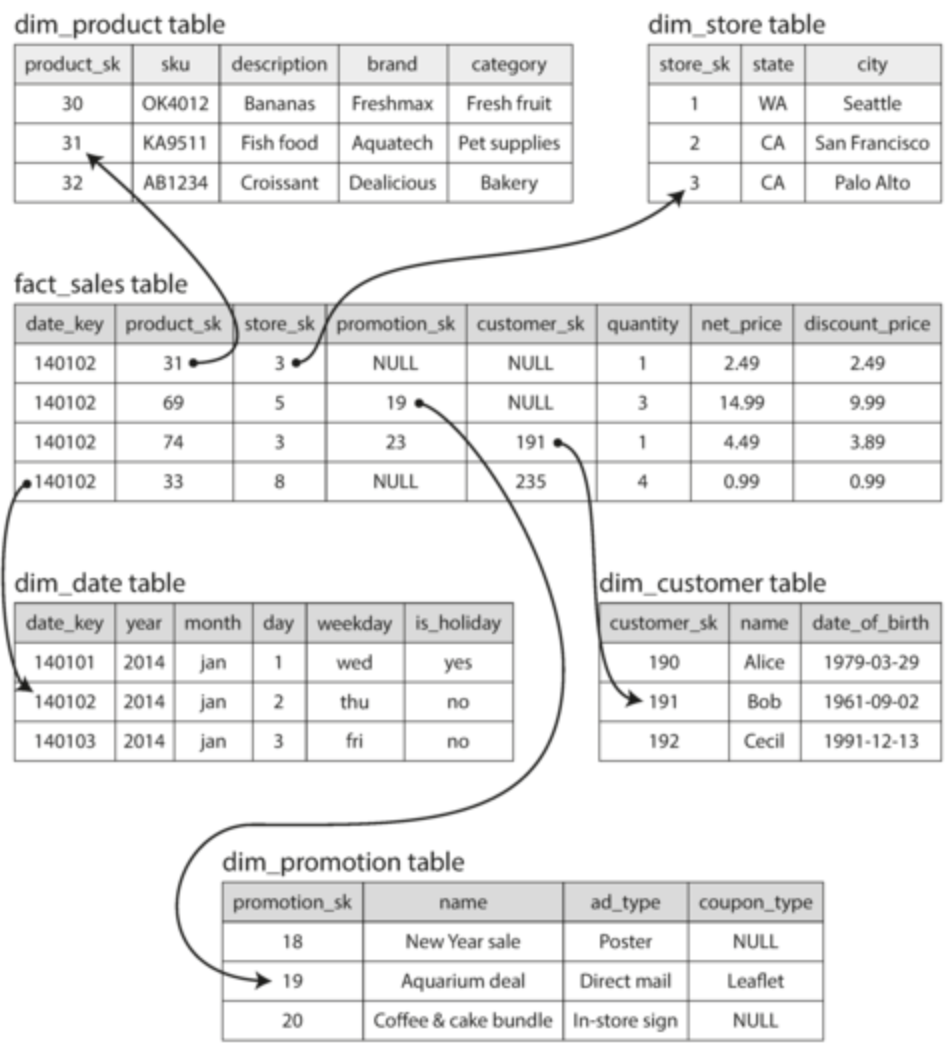

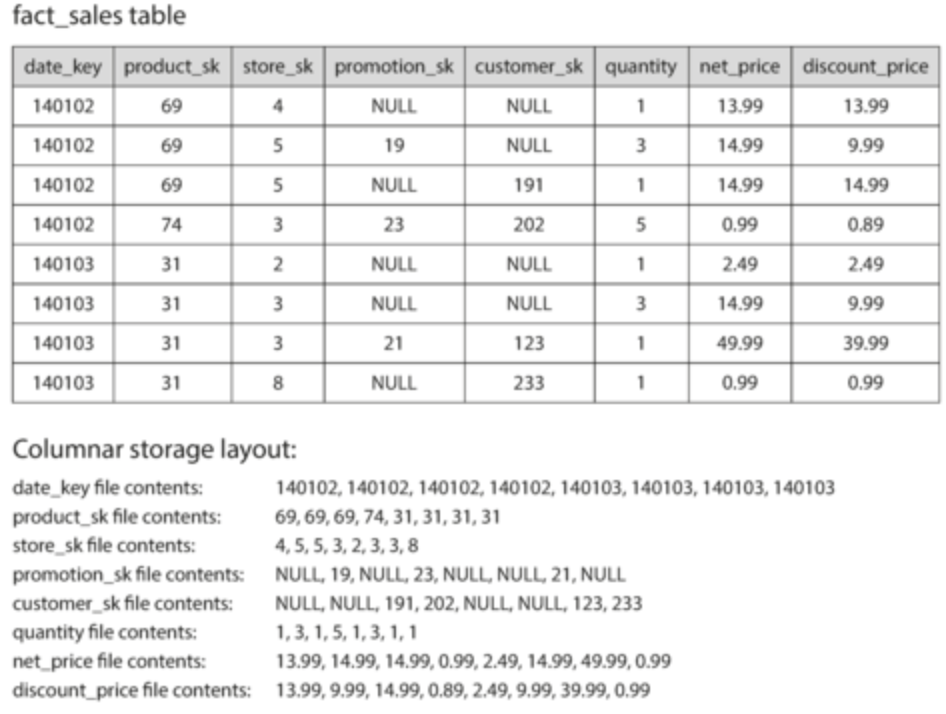

- Star schema: the go-to model for data warehousing

- Fact tables: each row represents event that occurred at some time (eg. transaction, page view, page click)

- Usually huge tables (petabytes large)

- Dimension tables: stores foreign key references from fact table that has the actual information for the foreign key. (eg. product types, special dates)

- Fact tables: each row represents event that occurred at some time (eg. transaction, page view, page click)

- Snowflake schema: dimensions broken down into sub-dimension table, but this may make it complex for the analyst to query, star schema is preferred

- Why is it called star schema? If you visualize fact and dimension table relations, it will look like a star

Column-Oriented Storage

- Problem: really hard to query petabytes of data on fact table

- Whenever we have these issues, look at the common usage patterns. It can help us optimize

- In this case, the common usage for fact tables is that we only need a couple of columns. We don’t need all 100+ columns in a fact table

- OLTP method: just index on date, but you still need to take all these rows from disk, parse, and filter. This takes time!

- OLAP method: store all values from each column together, saving lots of work

- Side note: you will see Parquet mentioned a lot for data. Parquet is a columnar storage format that supports document-based models for non-relational models

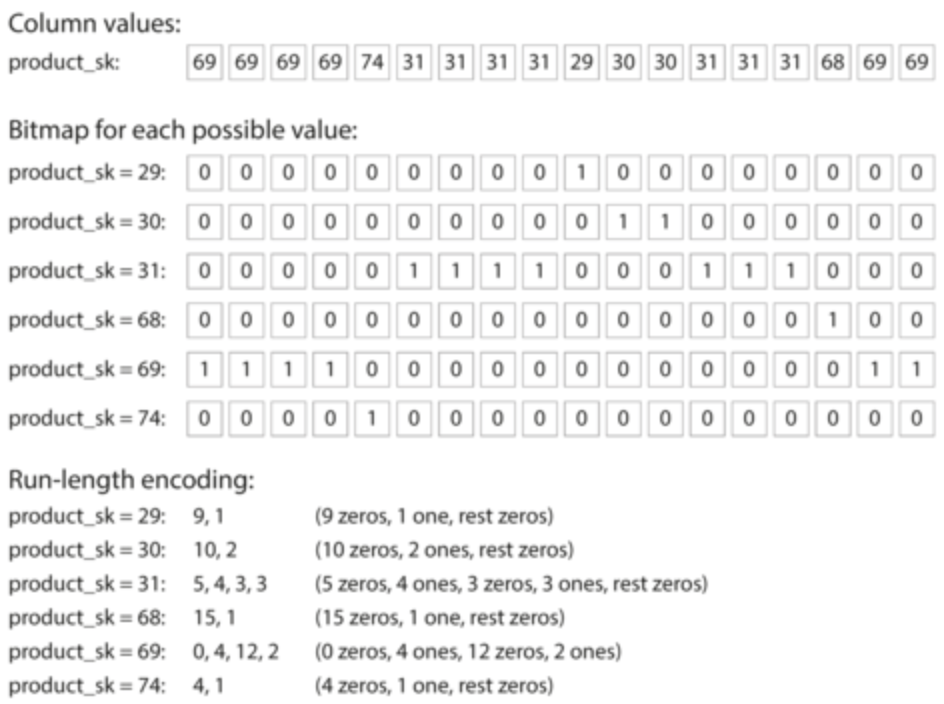

- Column-oriented storage can be compressed via bitmap encoding

- Again, the common use case is that we have lots of lots of rows, but each column has way less distinct rows (eg. billions of transactions, but only 100,000 distinct products)

- Solution: create a bitmap for each distinct value. If row has value, mark it as 1 in the bitmap. Tend to have a lot of zeros, so can even run-length encode

- Processing is faster because you can use bit operations

- Cassandra and HBase are not column oriented: they use the column family model where all columns in a column family are stored together with a row key with no column compression

- Column-oriented storage works better with CPUs and can fit comfortably in L1 caches and very easy to do bitwise operations on a large set of data rather than per row (known as vectorized processing, much like R language vector operations!)

- Sorting: order doesn’t matter too much but columns must be linked (i.e. cannot sort one column but not sort the other)

- You can set up DB to insert based on a predefined sorting order, like date

- Also lends itself well for compression: can use runlength encoding on sort column

- Some DBs even store data in multiple sorting orders

- Downside: writes are more difficult than row-oriented DBs

- One way out of this is to use in-memory data structures and only periodically update warehouses. Query engine has to merge results from DB and in-memory

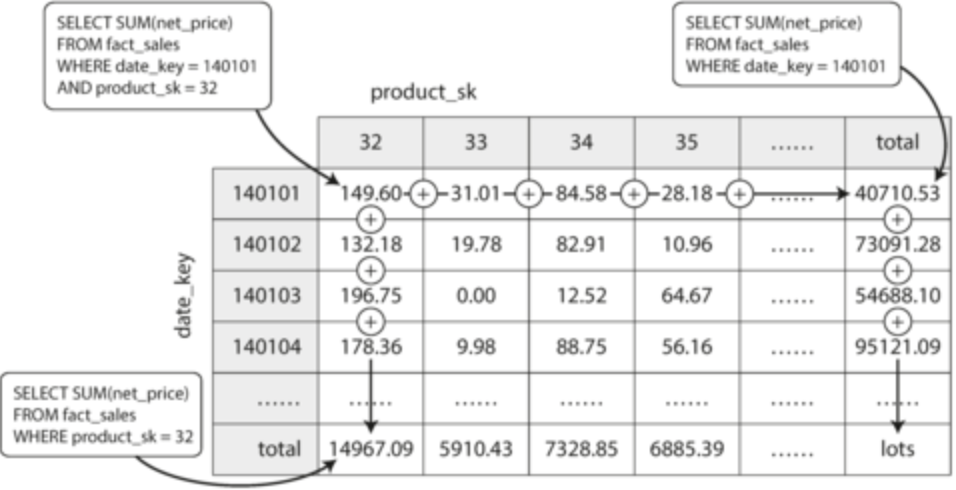

- Materialized views: common use case is to use some aggregation (eg. SUM, COUNT, AVG). Store the result of these common queries in a table and pull

- Issue: if the data changes, the views need to change too. Not great for OLTP

- Can use data cubes to store data across dimensions , but much less flexible because query is predefined.

- Most warehouses keep as much raw data and use views for very common queries

Ch. 4: Encoding and Evolution

- Due to evolving business needs, we would need to change schemas

- If it was a relational model, we need to use schema migrations

- If it is a schema-on-read model (schemaless), need to handle old data that doesn’t conform to latest changes

- Code changes due to evolutions shouldn’t happen instantaneously. You want to roll it out gradually if it’s on the backend (per node) or do small updates

- This means that backward (new code can handle old data) and forward (old code can handle new data) compatibility is important

- Data is either contained in memory through optimized data structures or needs to be encoded if written on a file

- Encoding: in memory DS → file. Also known as serialization/marshalling

- Decoding: file → in memory DS . Also known as deserialization/parsing/unmarshall

- Many languages have their own way of encoding data structures. This isn’t great because it ties you to use a specific language, it is not the most secure, not always forward compatible and not efficient

- Generally, don’t use this! Use standard encodings

- Standard encoding formats: JSON, XML and CSV. Issues include

- Encoding numbers is difficult, such as floating numbers or even strings

- Doesn’t always support binary strings, so need to encode using Base64

- Schemas for these are not widely used, so intrepretation becomes difficult

- Within organizations where it’s not necessary to use standard encoding, you can use binary encoding (eg. BSON)

- Popular binary encoding: Thrift (open sourced by FB) and Protobuf (open sourced by Google)

- Requires schema for encoding, which then is used to refer to fields within documents

- If the schema changes, any fields that do not map to the schema are simply ignored. Shouldn’t change required fields. You can change data type, but that might cause truncation

- Apache Avro: has schema but does not refer to fields within documents. This gives further compaction but changes to schema will render document useless

- Got around this issue by using the writer’s schema and the reader’s schema and resolving differences

- Requires having database of schema versions (generally a good practice) and appending schema version to data

- Much easier to dynamically generate schemas as it doesn’t rely on field references

- Protobuf and Thrift, on the other hand, are slightly better for code generation

Modes of Dataflow

- Often times, you have several processes interacting with the databases, some running new code, some old. It’s important to think about forward and backward compatibility

- Schema evolutions and migrations allow the data to look like it was written through one schema

- Make sure encoding of data while doing snapshots (for purposes like warehousing) is the same! Don’t change from Avro to Protobuf thinking things will be ok

- Backend servers can also be clients to other services, like databases. Thus, we have started to move towards service-oriented architecture or microservices where several smaller services make requests and communicate with one another

- Services define own API endpoints provided by business logic

- Design goal of microservices is to make it easier to change and maintain services as they are independently deployable and evolvable

- This means that you should be always thinking about forward and backward compatibility, as old and new versions of services might be in the same instance

- How do you talk to all these services, servers and databases? Several protocols, but will go over HTTP and RPC

- HTTP:

- SOAP paradigm: XML based, avoids using HTTP and tries to be independent

- Uses WSDL (XML-based language) to access remote service using local classes and methods, which is useful for statically typed languages

- Usually pretty complex messages, difficult integration

- REST paradigm: one URL for one resource, simple data formats and uses HTTP methods of caching, auth and content type

- Can use services like Swagger to document endpoints

- SOAP paradigm: XML based, avoids using HTTP and tries to be independent

- RPC:

- Essentially makes request to remote service and looks the exact same as calling a function in your language (known as location transparency)

- Flawed: making network calls look like local function calls is weird because network calls can easily fail and are unpredictable, remote calls can be hard to debug, wildly different response times, can’t pass objects/pointers like function calls, can be difficult for cross-languages

- Not going away: Thrift and Avro have RPC support, gRPC is RPC implementation using protobufs (also supports streams)

- Typically used for internal company services, not used at all for public APIs

- These protocols evolve server-first, so requests must be backward compatible and responses must be forward compatible

- Since these are communication protocols and cannot force people to change their method of communicating using APIs, compatibility is usually permanent

- Need to version API URLs or keys

- Last method of data flow is message passing. Similar to RPC where client request (message) sent to another process with low latency, but there is a middleware like a DB known as a message broker/queue which stores temporarily

- Message broker can actas a buffer, anonymizes user, history of previous messages, decouples sender and recipient

- Key difference: sender doesn’t expect to recieve reply through the same channel. It is completeley asynchronous

- Examples of message queues: RabbitMQ, ActiveMQ, Kafka

- Flow: sender sends message to particular queue/topic. Consumer/subscriber to that queue will get product of action. You can chain consumers to publish another message to another queue, but fundamentally a one-way transaction

- Actor model: actor process represents one entity (can have some local state) and merely communicates with other actors, avoiding concurrency issues. Publishes communications to message queues. Can be distributed. Ex: Akka, Orleans, Erlang OTP

Part 2: Distributed Data

- Distributed data all about how to get multiple computers to store and retrive data

- Why do you want multiple machines?

- Scalability: single machines likely won’t be able to handle much load, so you need to spread across different machines

- Fault tolerance/high availbility: if one machine goes down, another can act as redundancy

- Latency: reduces latency if you have multiple machines around the world rather than all users using one computer in a far-away place

- Vertical scaling (shared-memory architecture): make your existing machine OP (more CPUs, more RAM)

- Usually really expensive and limited fault tolerance

- Shared disk architecture: multiple machines but they use the same disks for data, but also limits ability to scale

- Horizontal scaling (share-nothing architecture): each machine (node) has own CPU, RAM and disks. Coordination done at software level

- No special hardware, so costs don’t grow as high. Latency and availbility are better

- Cons: the developer needs to be really wary and understand what they are doing. Easy to mess up and cause downstream issues

- How do you distribute data across multiple nodes? Two methods:

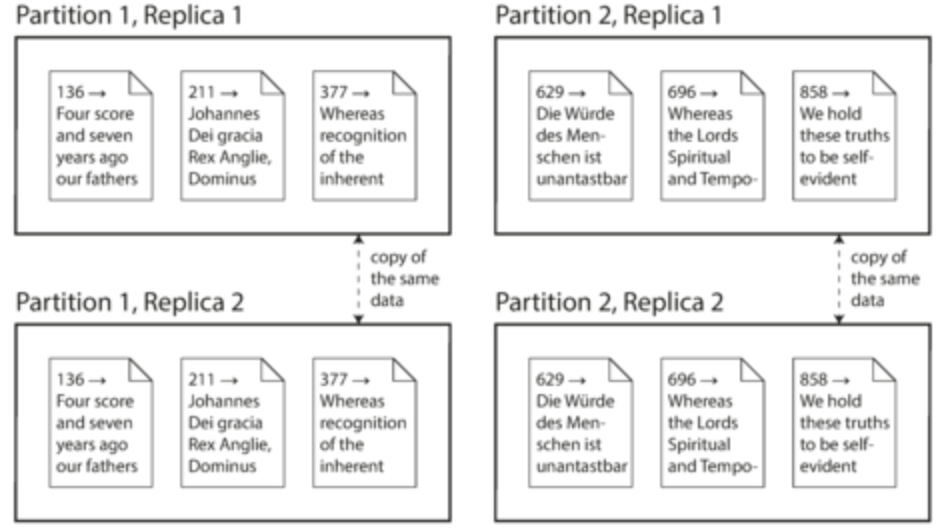

- Replication: keep copy of same data on multiple nodes, providing redundancy. Also improves performance

- Partitioning: split big database into smaller parts and assign parts to different nodes (known as sharding).

Ch. 5: Replication

- Major assumption: data is small enough that each machine can hold copy of entire dataset

- Replication is difficult when dealing and synchronizing changes to data across nodes

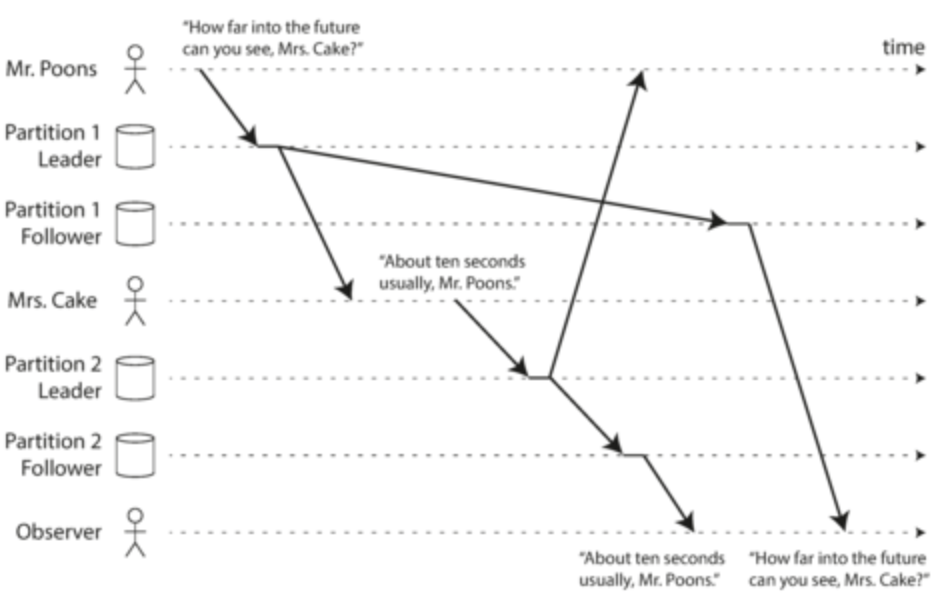

- Three approaches: single-leader, multi-leader and leaderless

- Replica: a node that stores a copy of the database

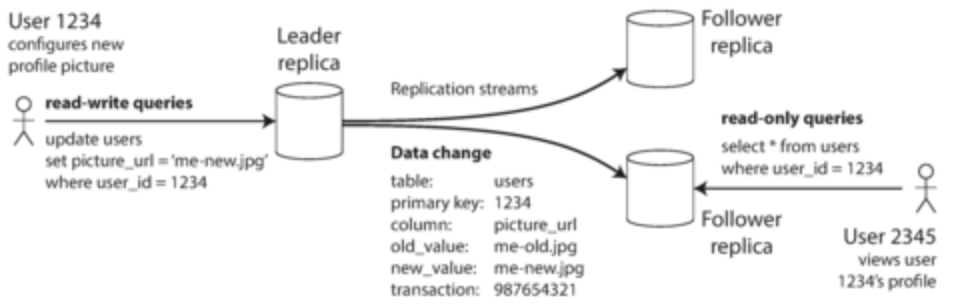

- Leader-based replication:

- One replica is designated as leader. All writes handled by leader

- All other replicas are followers (read replicas/slaves). Leader will send changes in log and follow takes log, updating local copies based on order set in log

- Reads are handled by all replicas

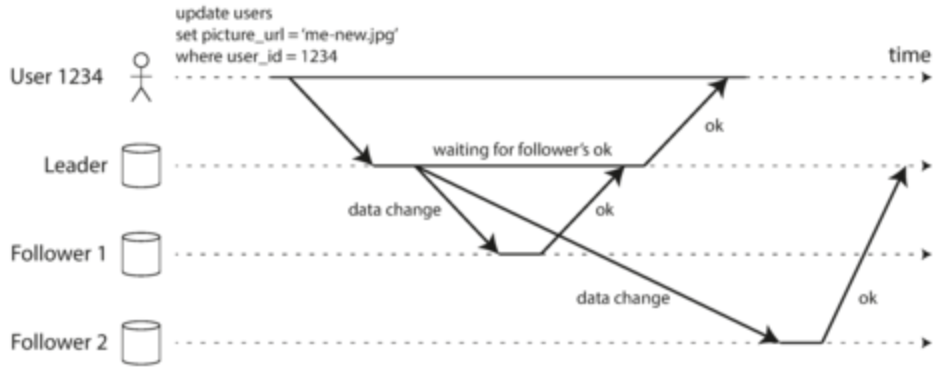

- Synchronous replication: leader waits until synchronous follow is also completed.

- Pros: follower guaranteed to have up-to-date copy.

- Cons: if follower crashes, leader is blocked because it has to wait

- Asynchronous replication: leader does not wait but follower will eventually update

- Usually 1-2 nodes are synchronous and everything else is async

- Can be semi-synchronous: if synchronous node starts to slow down, make an async node into a sync node

- Usually leader-based replication is completely async. Not guaranteed to be durable as leader could fail and writes lost, but this is usually OK because very little lag

- To add a new follower:

- Take a snapshot of the leader’s database and copy to new follower

- Follower connects to leader and requests data changes since snapshot taken

- Once follower has finished backlog of data changes, it’s good to go

- Handling node outages:

- If follower fails: follower can look at log of changes that it has locally, restore database, and then connect to leader for changes since it was down

- If leader fails: perform failover

- Determine that the leader has failed: since nodes talk to each other, you can configure an alert based on timeout (also known as heartbeat)

- Choose a new leader: nodes can either do a majority vote or appointed by a previously elected controller node. We want a node that is the most up-to-date

- Reconfigure so writes sent to new leader and prevent old leader from taking control if it comes back

- Issues with failover:

- Data may be inconsistent with writes recieved by old leader and writes stored by new leader. Usually old leader writes are discarded

- Data can be inconsistent with other technologies, like Redis

- Split brain scenario could arise where two nodes think they are both leaders. Need mechanism to shut one node down if this happens

- Choosing timeout time is tough. Some nodes just slow down due to spikes

- Replication logs: usually handled by DB

- Statement-based replication: every write request added to leader’s log and sends to followers.

- Where does it break down: non-deterministic function calls will have different values across followers, autoincrementing columns have to be precisely executed, side effects

- Too many edge cases, so not favored

- Write-ahead log shipping: log data and send it to followers

- Where it breaks down: if data format changes by some update, hard to configure followers to follow the new data format. Tightly coupled to storage engine

- Logical (row-based) log replication: use a different file format from storage engine that contains just enough information to identify data inserted/updated/deleted

- Pretty easy to use, especially for external applications

- Trigger-based replication: used when you don’t want the DB to handle replication and you want control

- Register code to automatically trigger upon data change. You can use this code to log into a separate table

- Great over head and more prone to bugs

- Statement-based replication: every write request added to leader’s log and sends to followers.

Problems with Replication Lag

- If we do asynchronous replication, we could easily distribute reads across multiple nodes. However, we then run the risk of having old data

- However, this is temporary. If we wait a while, it will be eventually correct. This practice is known as eventual consistency

- Obviously we want to keep the lag down, but if we are operating at capacity, we will run into several different issues

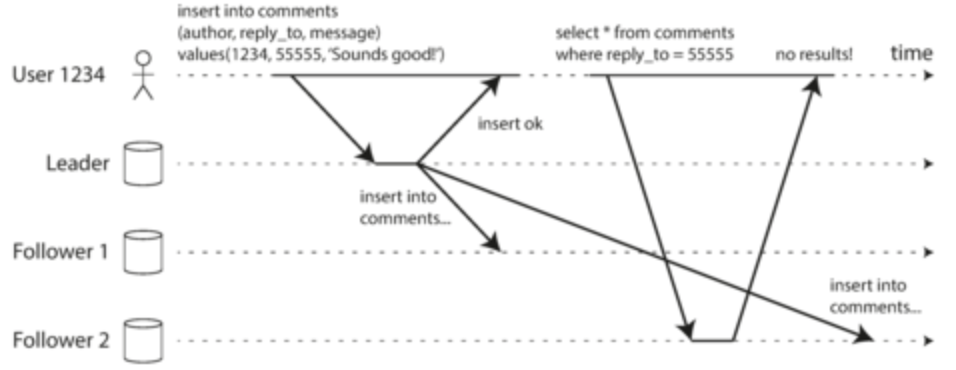

- Read-after-write consistency: want user that just wrote something to DB to be able to see it right after. No guarantee for any other user seeing the new data (eg. kinda like comments on social media. We want to immediately see our comment when we write it). Implementation:

- If only a few things are editable, then just configure the user that just wrote to the DB to read from the leader

- If many things are editable, you could direct all reads to leader for 1 minute after the last update or direct user to up-to-date replica

- User can have some sort of timestamp to find up-to-date replica

- Complication: if replicas distributed across multiple datacenters, then accessing the leader will create delays. May also want to have cross-device read-after-write consistent (created comment on Insta on iPhone, want to see comment on iPad)

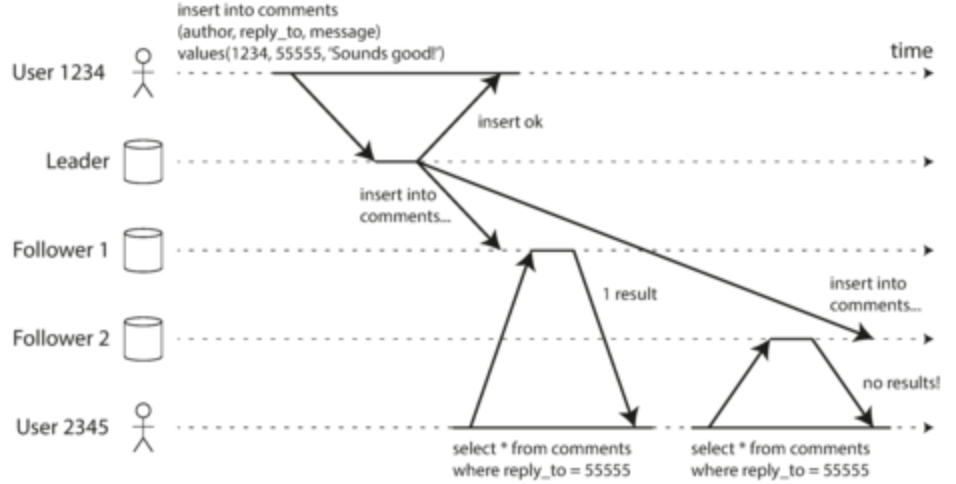

- Monotonic reads: guarantees that user will not see old data after they have previously read new data

- Easy implementation: user only reads from one replica

- Consistent prefix reads: if sequence of writes happen, then writes should appear in same order when read (eg. A asks question 1, B answers with answer 1. If A has long lag and B has short lag, then it would look like B answered the question before A even asked! This shouldn’t happen in DBs either)

- Issue with partitioned DBs, as partitions operate independently so no global ordering of writes

- Try to make sure that related writes are sent to the same partition

- Think about how your system can handle eventual consisteny if the lag takes hours. Try to design a strong of a consistent system as possible if this will detract from users

- Developers will have a tough time handling in application code. We will go over methods later

Multi-leader replication

- Allow more than one leader to handle writes in order to have some sort of redundancy. Each leader will act as a follower to the other leader

- Situations where this would be useful:

- If you have multiple datacenters, you probably don’t want all writes going to one replica because this creates additional lag. Instead have a leader in each datacenter. Within datacenters, it acts as a single-leader replication. Across datacenters, replicate between leaders

- Offline functionality needs multi-leader replication, with your device temporarily acting as leader. Sync when they are back online

- Collaborative editing is not really a data problem but it follows the same principles of multi-leader replication, with each contributor as a leader. Probably want to lock database on a keystroke basis when editing so you don’t hit too many conflicts

- Issue: writing to same data across multiple datacenters will create write conflicts and lots of configuration is needed

- Handling write conflicts:

- Synchronous detection isn’t great because you lose out on the main advantage of multi-leader replication of each replica accepting a write

- Better if you avoid them completely by routing all writes for a particular record through the same leader

- If you still cannot prevent concurrent writes across multiple leaders, you will need to use async resolution. Specifically, you could have an ID for each write and throw away all writes to same record across leaders except for the highest one (basically last write wins)

- Can also prioritize based on replicas, merge the conflicts or ask user to resolve later

- Most multi-leader replication tools give you custom ways of handling write conflicts

- Note: even if some transaction has several writes, write conflict resolution is not done on a transaction level. It is done on a write level

- Replication topology: describes how leaders replicate writes

- To prevent infinite writes for one record, each write has list of unique leaders it has seen and is discarded when all leaders have seen the write

- Most common topology is all-to-all: all leaders replicate to all leaders

- Other topologies are not as fault-tolerant and all-to-all is susceptible to writes being in jumbled order (i.e. network speeds vary)

Leaderless Replication

- There is no leader that takes writes; every replica can accept writes. No leader to set write order

- Ex: AWS Dynamo, Cassandra, Voldemort

- Some implementations also have a coordinator node that controls where writes are sent, but does not enforce write order

- In a leader-based replication strategy, if the leader node is down, there is some failover. There is no such concept in leaderless replication.

- The client will send one write request to several replicas and get a 200 response when at least some of the replicas are able to handle the write (even if others cannot)

- Because there’s always a possibility that some nodes didn’t catch the write, we could potentially get stale data. To prevent this, we also have 1 read request hit several replicas. Different response data might return but you can use version numbers to choose which data is most up to date

- To catch up on writes, we can use two techniques:

- Read repair: on read, we can tell which server gave us old data by comparing versions across different nodes. We then write the new data upon read

- Anti-entropy process: background process that checks for differences in data across node and copies missing data, but slow and does not enforce order

- How do you choose the number of replicas that need to respond successfully upon write? Let n be the number of nodes, w be the number of nodes that respond successfully upon write and r be the number of nodes that are queried on read

- If w + r > n, then we can expect to get up-to-date data on read (quorum)

- Quorum reads and write: values of w and r such that above is true

- Typically all n nodes are written and read, but w and r is how many we wait for success

- Typically, w and r are majority of n, but this doesn’t need to be true. As long as the set of written and read nodes overlap, we should be good

- This is why EVEN THOUGH quorum is reached, we can still get stale reads (r and w nodes don’t overlap)

- Other edge cases: writes at exact same time are not handled (will prolly merge), reading at same time of writing may return stale data, writes that failed on some nodes but not on others would not be rolled back so you get inconsistency, can lose data if node fails when its the only node with updated data

- Setting w and r to be low decreases latency and get higher availability since we don’t need to wait for so many nodes to guarantee the write went through

- Leaderless replication is only used if the application can tolerate eventual consistency

- Leader-based replication offers metrics to monitor replication lag since you can easily check how far followers are with their backlog. This is much more difficult for leaderless replication since there is no leader to set order! How can you tell if a follower is caught up?

- Sloppy quorum: during outages where fewer than n nodes are available, you put the data into a node where it shouldn’t be.

- After the outage, use hinted handoff to write back to the node you were supposed to be in

- Not really quorum because you may still read old data before handoff complete

- Leaderless replication suited well for multiple datacenters since it guarantees high availability

- Client sends request to all nodes, but only waits for quorum in local datacenter rather than wait due to network latency

- How to handle concurrent writes:

- Last write wins: attach timestamp to each write when sent to nodes. When you read, you just use the write with the largest timestamp and discard the rest. Not a very durable solution as writes might get lost (if you’re ok with that)

- You can use versioning of writes, but you need to do some merging

Ch. 6: Partitioning

- For extremely large amounts of data or high query throughput, replication will not suffice. We need to break up the data or partition/shard the data

- Think of each partition as a tinier version of the database, although you can touch multiple partitions at the same time

- Normally want each record to belong to only one partition

- Why? Partitioning is very scalable: you can put different shards on different nodes and you can support a lot more queries (if you design it correctly, each query should only touch one partition)

- Partitioning is usually combined with replication for redundancy and fault tolerance

- A node can store multiple partitions. If you follow leader-based replication, one node can be leader for one partition, other nodes can be leaders for other partitions

- Replication logic should be indepdent of partition logic

![[Screen Shot 2021-05-05 at 5.42.34 PM.png|]]

- Goal of partitioning: we want to spread data and query load evenly across nodes. We don’t want load/storage to be skewed

- Hot spot: partition with disproportionately high load

- Simple method: distribute randomly. Problem: you don’t know where the data is!

- Better method: partition by key range

- Assign one node to one range of keys, another to another range of keys. That way, you only need to know the boundaries of each partition to figure out where it is stored. Think of it like a print encyclopedia: all information related to A is in one boko, another is in B

- Ranges of keys don’t need to be evenly spaced, the data needs to be evenly spaced. Again, print encyclopedias usually have a volume for A and B and another volume from T-Z!

- Ranges chosen by DBA or automatic

- Within each partition, you can store keys in sorted order for easy range using SSTables or even use concatenated indices

- Issue with key range partitioning: certain access patterns can lead to hot spots

- Take example of data keyed by date. The partition of the current day will be a hot spot as all the data for that data is written into one partition

- Solution: partition the partition (split it into smaller chunks)

- Rather than using key ranges, many DBs use hashes to take skewed data into uniform data. Each partition takes a range of hashes rather than keys

- This usually is good at distributing keys among partitions

- Problem: range queries are harder since you need to query all partitions

- Solution: use compound primary keys. The original primary key determines the partition but the compound primary keys are just columns that are concatenated for easy sorting

- Partitioning by hashes cannot completely remove hotspots. Let’s say we are a social media platform and we partitioned based on user IDs. Particularly popular celebrities may get tons of writes to the same hash key!

- Simple solution: partition hot key further by adding random numbers, but this makes queries more difficult and requires bookkeeping

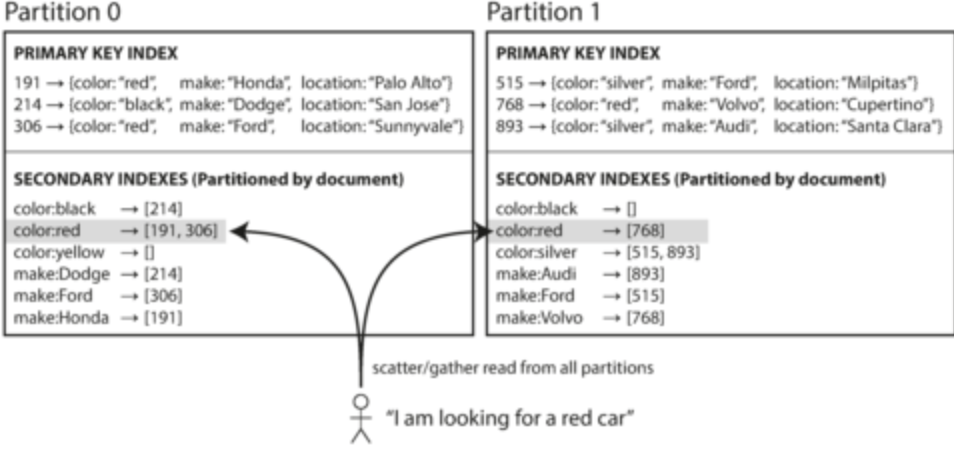

Partitioning and Secondary Indices

- What we have currently discussed only works if we are referring to data by the primary key. We need to have secondary indices that are not unique identifiers

- Document-based partitioning: create a secondary index that contains a list of all document ids for a particular value of the secondary index for each partition (local index)

- Problem: will probably need to query all partitions to get all data (scatter/gather)

- Used in Mongo, Elasticsearch, Solr and Cassandra

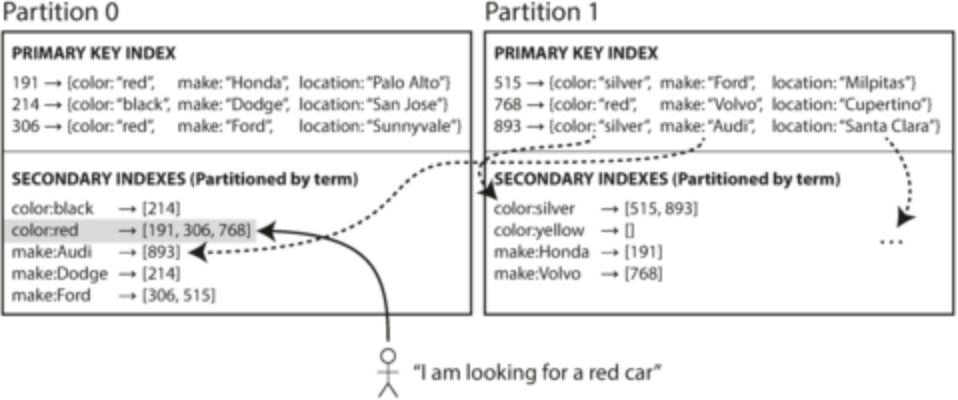

- Term-based partitioning: create a global index for secondary indicies but partition the index as well

- Ex: color is secondary index. Document-based partitioning would index for each partition of the database. Term-based partitioning would partition a global index across partitions

- Reads are faster, but writes are slightly more complicated because need to write to several partitions since secondary indices are partitioned independently of main data

- Document-based partitioning: create a secondary index that contains a list of all document ids for a particular value of the secondary index for each partition (local index)

Rebalancing Partitions

- Sometimes need to transfer data and requests to different nodes, known as rebalancing

- Requirements we need to meet:

- Load should be shared fairly by all nodes after rebalancing

- While rebalancing is happening, we want to continue to accept reads and writes

- Don’t move more data than necessary in order to make rebalancing fast and minimize network & I/O load

- Never distribute hash using mod N (where N is the number of nodes) because if N changes, you need to change a lot of keys to different nodes

- Eg: let’s say we have 10 nodes in the beginning. If we distributed by taking the hash % 10, then we know the node it should go into. However, if we add 5 more nodes, then we need to recalculate where all the keys go

- Simple solution: create more partitions than nodes and assign multiple partitions on one node (fixed partitioning).

- When we add more nodes, we can just move partitions until load is balanced

- You need to know the number of partitions at the outset, so choose the maximum number of partitions you could possibly handle while not being a burden

- Need to make sure partitions are not too big or too small, otherwise movement will cause unnecessary problems. However, this is hard to predict when you start

- Dynamic partitioning: split partitions if they become too big and merge when they get too small

- To rebalance, we simply take the split partitions and move one to another node

- Issue: empty database will only have one partition, so waste of resources of other nodes

- Solution: pre-split keys into partitions

- Used for both key-range and hash-based partitioning. MongoDB uses this

- Partition proportional to nodes:

- For dynamic partitioning, the number of partitions is proportional to the dataset. For fixed partitioning, the number of nodes is proportional to the dataset

- We could make the number of partitions proportional to the number of nodes so you have a fixed number of partitions per node

- Partition size grows as dataset grows without change in nodes, but if you change node number, partitions become smaller

- Keeps size of each partition relatively stable

- When new node joins, chooses fixed number of existing partitions, splits and takes ownership of split

- Cassandra uses this but it requires hash partitioning

- Rebalancing should have humans monitoring because there are several details

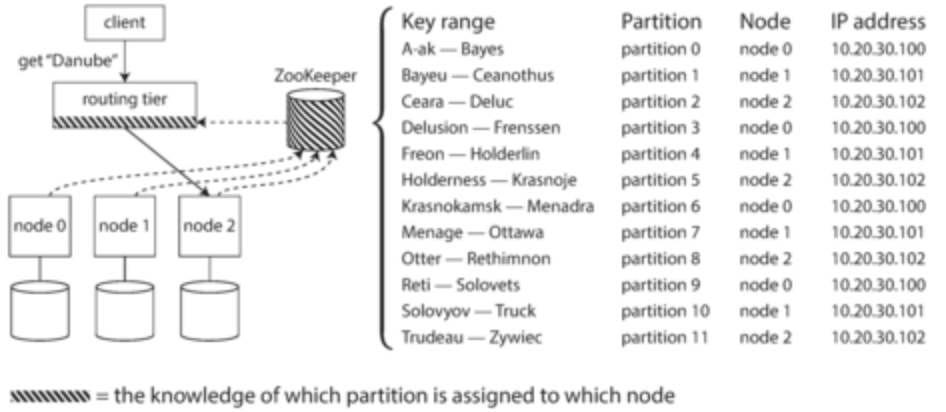

Request Routing

- Service discovery: across distributed system, how do you figure out which node to access?

- In our case of partitioning, how do we figure out where to read and write?

- Options:

- 1: any node can serve request, but each node can direct to other nodes for correct information (like round-robin tournaments)

- 2: Have a partition-aware load balancer that can direct request to correct node

- 3: Client already knows partition and directly connects

- Many systems use services like ZooKeeper to keep track of cluster metadata such that requests can be correctly routed

- Other services (like other nodes or the client themselves) can subscribe to Zookeeper and change data as necessary when Zookeeper changes

- Some systems like Cassandra use a gossip protocol, so when partitioning changes, all nodes are informed

- For analytical processing in warehouses, we often use massively parallel processing since we use lots of joins and aggregations

- The MPP query optimizer takes a complex query and splits into several stages and partitions such that they can be independently taken care by database nodes

- Spark works on similar principles

Ch. 7: Transactions

- Transactions: group several reads and writes into one operation. Either the entire transaction suceeds (commit) or fails (abort, rollback)

- This allows the application to safely retry without worrying about data already being in the database

- Almost every relational database supports transactions. However, many NoSQL solutions sacrificed transactions in an effort to create scalable DBs

- ACID has different implementations across DBs, so not a great guarantee on behaviour

- Atomicity: basically transaction behaviour (commit or fail)

- Consistency: invariants of your DB are not violated. This is on the application to make sure consistency is handled

- Isolation: concurrent transactions don’t step on each other’s toes, they are isolated from each other. One commit at a time (serializability), not multiple at ones

- Durability: any data written will not be forgotten even if hardware crashes. Involves nonvolatile storage and write-ahead logs for recovery

- Atomicity and isolation also apply for single objects: you want the entire object to be comitted!

- Atomicity can be implemented using recovery logs and isolation can be implemented via locks (only one process can access object at any time)

- Multi-object transactions are much more difficult for distributed data. Best we can really do is coordinate and use foreign key constraints

- Up to application developer to handle errors and retry logic. Have to be careful:

- If network error causes error but transaction succeeds, retry would duplicate data

- If error is due to overload, retry would make it worse. Use exponential backoff, limit retries or handle overload errors differently

- You don’t want to retry all errors (eg. constraint violations shouldn’t be retried)

- One transaction can have side effects (eg. sending email). If not properly handled, you could retry those side effects even if they were successfully sent on failure

Weak Isolation Levels

- Concurrency issues with transactions only comes to play if the transactions are hitting the same resource at the same time

- Serialization isolation is very strong isolation, but it often hits performance, so many databases have weaker isolation

- Weaker isolation is hard to understand and doesn’t protect against all concurrency issues

- Read committed: makes two guarantees - no dirty reads (only see data committed) and no dirty writes (only overwrite data that has been committed)

- Preventing dirty reads are important especially in multi-object transactions and when we need to rollback changes during a transaction

- Preventing dirty writes are important for multi-object transactions

- Pretty popular feature. Uses row-level locks that also stores previous committed versions of data to allow reads on records that are currently being written (but uses old committed data instead)

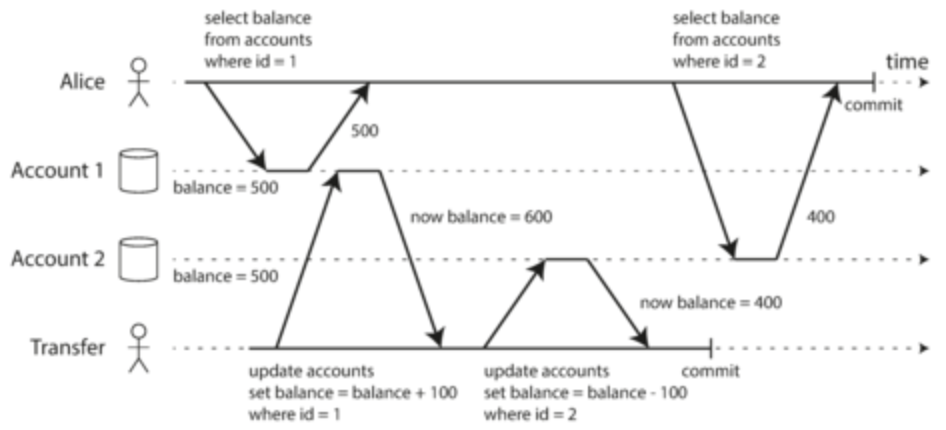

- Snapshot isolation:

- Read committed strategy allows read skew, where you read values in the middle of a transaction which may not make sense to the end user. Mix of new and old versions

- While this is usually a temporary issue, some situations cannot accept this: backups, analytical queries

- Snapshot isolation forces transaction read from consistent snapshot of DB. This prevents reads on mixed data as seen when having long transactions

- Popular feature as well. Only uses write locks and needs to use multi-version concurrency control to store snapshot versions