Introduction

Clubhouse has recently taken the Internet by storm with its new form of audio-based social media. First hearing about it from a friend, I decided to check it out. Although I am not a fan of most social media platforms, I was pleasantly surprised by the features on the platform and the quick adoption rate among my friends.

At the same time, I was busy reading Hooked by Nir Eyal, which describes an opinionated framework towards creating a habit-forming product. I decided to take this opportunity to analyze the features that contribute to the stickiness of Clubhouse alongside its immense growth.

Growth

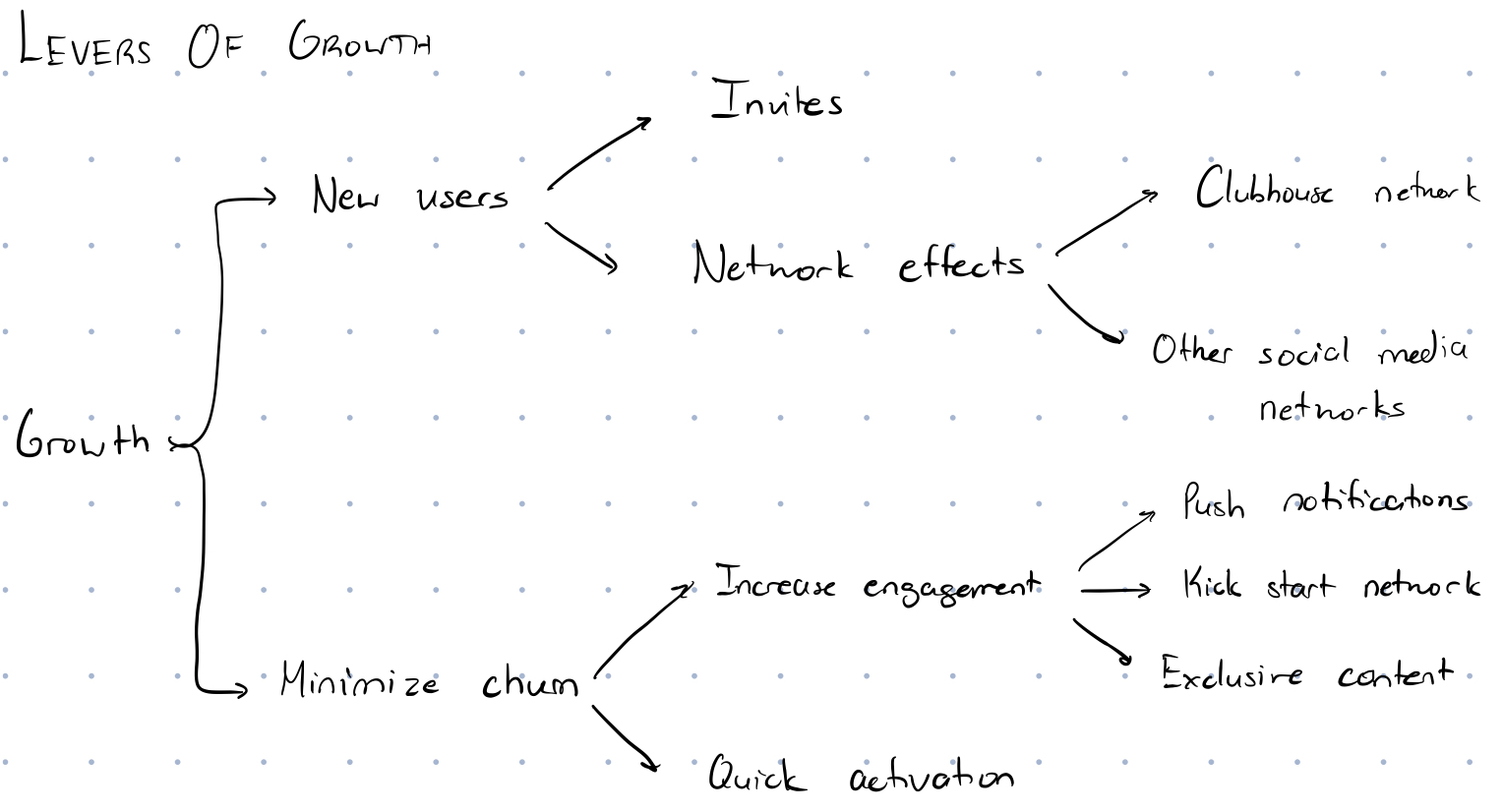

Let’s first tackle how Clubhouse grew so quickly. Here’s the framework that I used to identify the most potent levers of growth on the platform:

In order to maximize growth, there are two things the platform owner must do: maximize the number of new users coming to the product and minimize the number of users leaving the product. Let’s dive into the factors that contributed to maximizing new users on Clubhouse.

There were two major levers that I identified when it comes to increasing new users on the platform: invites and network effects. Clubhouse works on an invite-only model, where users who want to use the platform must enter a wait list. This invite-only model is boosted by invites, which allow new users to skip lines. I have previously talked about this, but invite-only models are huge catalysts for growth because they are a signal of scarcity, a quality that humans crave. Examples of other scarcity-driven business models include Supreme and Dispo, products that have become immensely popular because of percieved scarcity. This translates into growth pretty easily: demand goes up and more people clamour at the doors of the app, creating a flywheel. Another added benefit of an invite-model is that it creates social proof among its users. Exclusivity acts as a potent chemical in creating evangelists, as people have a need to show their social status as Clubhouse members.

This perfectly segues into the second major lever in increasing user growth: network effects. I have noticed time and time again that networks are the single biggest scale factor for new products. Clubhouse uses networks in two ways. The first way is what I call the ‘piggyback approach’: Clubhouse evangelists use existing social networks (notably Twitter) to attract more users. In this way, Clubhouse bypasses the cold start problem that many network-based apps face by simply using another social network. Isaac Newton puts it aptly, “If I have seen further, it is because I am standing on the shoulders of giants”. Clubhouse simply stands on the shoulders of other social media networks. The second use of networks in Clubhouse’s growth strategy is Clubhouse itself. All network effects occur when the benefit of the collective increase if another user signs up and this is quite clear with Clubhouse, where conversations can become more novel and interesting with more people. The network of Clubhouse itself self-propels growth, as others fear missing out and want to join in the fun.

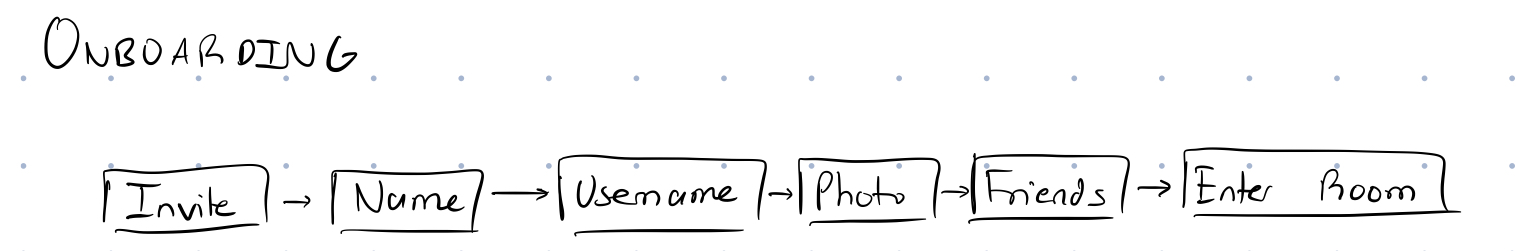

The second major lever of growth is retention, which Clubhouse seems to have minimized by optimizing user flows and onboarding. I identified two major levers of retention in the app: quick activation and increased engagement. To me, activation is simply the moment at which the user has their first ‘aha’ moment. For a truly user-capturing product, this ‘aha’ moment must come quickly after the user enters the product. Clubhouse perfected this by creating an incredibly quick onboarding flow:

That’s it. Just 6 steps and you’re in a room, or in other words, 6 steps until you realize the value of Clubhouse. Think about all the products that you use with an incredibly tedious user flow: these complex flows make you less likely to actually use the product and more likely to ghost. Simple onboarding leads to quick activation.

The next retention lever is high engagement. While the app uses a variety of different features to create high engagement, we can boil it down to three: push notifications, network kick starts and exclusive content. Push notifications are incredibly important to ‘push’ people to use their app. However, Clubhouse uses push notifications based on peer pressure: it notifies users if their friends are using Clubhouse. This prompts users to engage with the platform in order to talk to their friends, which leads to a flywheel of engagement. Another interesting part of Clubhouse is the network kick starts. Multiple companies have often struggled with the cold starts of networks and often resort to copying the network of Facebook and Twitter by simply importing these social graphs upon permission. Clubhouse does things differently: it uses the network of the person who invited the user in order to kickstart the network of the new user. This is a novel idea, as it is very likely that the network of your invite will be similar to your own network. In this way, Clubhouse bypasses blatantly copying social network graphs while also kickstarting your own network. The last and probably most powerful engagement lever is exclusive content. Because of the ephemeral nature of audio, Clubhouse can tap into FOMO in its audience as people realize that they must either be on the app to hear their connections speak or they must contend with never hearing them speak on the topic of choice again. This becomes a powerful forcing function of engagement as the content on Clubhouse will disappear the very second the discussion is over.

In summary, Clubhouse has a host of powerful features that have created a flywheel of extreme growth and engagement.

Habits

Habits are the holy grail for social networks. Network thrive on engagement and new content, and the only way to autonomously generate engagmenet is to create a habit-forming product.

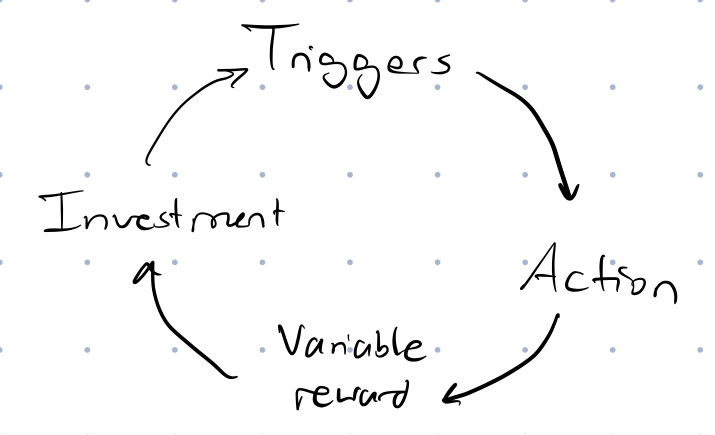

Nir Eyal’s book Hooked offered a framework for developing habits in products, somewhat reminiscent of the habit cycle proposed by James Clear in Atomic Habits. Ultimately, habits are generated due to the following cycle:

From my cursory analysis of Clubhouse, it seems like this habit cycle is already implemented in the app. Here’s how:

Triggers

We can roughly divide triggers into external triggers and internal triggers. External triggers use sensory stimulus, but internal triggers are from our mind. Here’s a list of external triggers on Clubhouse:

- Push notifications

- App icon (space on your phone that directly triggers you to click on the app)

- Text message invites from friends, which uses your relationships to trigger you to enter the app

- Tweets and post about upcoming Clubhouse talks

The holy grail of triggers are internal triggers, which are actions that you take in the app because of some internal emotion. This is where I believe Clubhouse needs to improve. It is trying to align itself with the emotion of boredom (which triggers users to use the app), but more work is needed on this front.

Action

Clubhouse has done an excellent job in this phase of the habit cycle. As mentioned in the section on growth, the app uses extremely simple flows to create high engagement rates, since it is extremely simple to start or join a talk. Clubhouse could improve on this part of the cycle by testing out different framing. For example, Clubhouse could look into using social proof to make these actions more enticing (eg. x of your friends are in this Clubhouse). Overall, I found Clubhouse delivered exceptionally in creating simple and enjoyable actions.

Variable Reward

Variable reward is what makes the habit loop so powerful. It is not just enough to reward the user; the reward must change randomly so that users keep coming back. Clubhouse already has variable reward ingrained in their product: conversations. Some conversations are incredible while others are boring. Furthermore, there is no way of predicting this beforehand, making it an extremely sticky product. Clubhouse could improve variable rewards by including a ‘like’ feature on each talk, incorporating variable social reward as well. This can even play a part in discovery, as higher-liked talks are ranked higher in the discovery algorithm.

Investment

Inherently, the product is based off social investment: you will need to speak in order to contribute to the app. Knowing that your voice and thoughts have been broadcasted to individuals across the world can be exhilarating, making the app quite sticky. Furthermore, Clubhouse embeds triggers within investments, especially when you add someone as a Clubhouse friend. When this friend joins another Clubhouse, you will get a push notification, starting the cycle all over again. I believe that Clubhouse has room to improve here, especially by taking advantage of the IKEA effect: people become more attached to products which they ‘built’ themselves. Features like curated discovery or a Clubhouse profile would possibly bring this app to the next level in this phase of the habit cycle.

Conclusion

Clubhouse is a great example of an app that has maximized its growth levers and has begun the process of creating a truly sticky app. I am excited to see the features that the Clubhouse team will be implementing soon and how that will affect its growth and app habits.

I want to end this post off by encouraging readers to really pay attention to the apps that they are using. Many apps use these habit loops in order to create stickiness; whether this is good or bad is a judgement left up to the reader. A broader understanding of how apps are able to create habits would hugely improve public discourse, our usage of technology and our mindset as we build new products.

References

https://www.theappfuel.com/examples/clubhouse_onboarding https://www.amazon.ca/Hooked-How-Build-Habit-Forming-Products/dp/0670069329