How I landed into log parsing

The story all starts with joining an engineering program in Canada. All engineering students are required to complete a capstone project as a demonstration of the knowledge acquired during the course of our degree. The SE capstone has always been a highlight of the program, as some of our most notable projects, like UW Flow and contributions to the Rust compiler, have stemmed from this requirement.

FYDP usually starts in 3B for SE students, where we are initially asked to try a bunch of different, small projects over the course of a few weeks. This is an opportunity for us to experiment and determine what projects we wanted to commit to and whether we would enjoy working with our groups. My group worked on 3 projects:

- We made a prototype app of a clothing fitting app that could across multiple stores

- Contributed to the Airflow UI

- Contributed to Pytorch’s Metal modules

From these experiments we learned a couple of things:

- Contributing to open-source is quite fun since there are a lot of problems out there. However, contributors and maintainers are quite busy, so feedback loops are quite long. If you want to contribute a sizeable feature to an open-source repository for a school project, timelines might not align

- Our group worked really well together. We were relieved to find this, because team chemistry is arguably the biggest risk of FYDP. If your team cannot get along, FYDP will be an annoying experience.

Although FYDP would start formally in our 4A semester, we needed to decide on a project before the term started as everyone on my team was leaving for exchange; collaboration would be difficult across international boundaries. We spent the summer before 4A searching for ideas, coming up with quick prototypes to see if anything stuck. The most important criteria we were looking to hit was to find a project that all 3 of us liked. If one of us didn’t like an idea, then building a product would be exceptionally difficult. We spent a few weeks on this making no headway until our professor mentioned a new prof (Prof. Weiyi Shang) coming to UWaterloo who specialized in software engineering research and was looking for some undergraduate student help. We scoured his published research, saw some common trends and proposed a couple of research ideas that all of us liked. He saw our ideas and proposed one back: productionize his log parser.

Our work

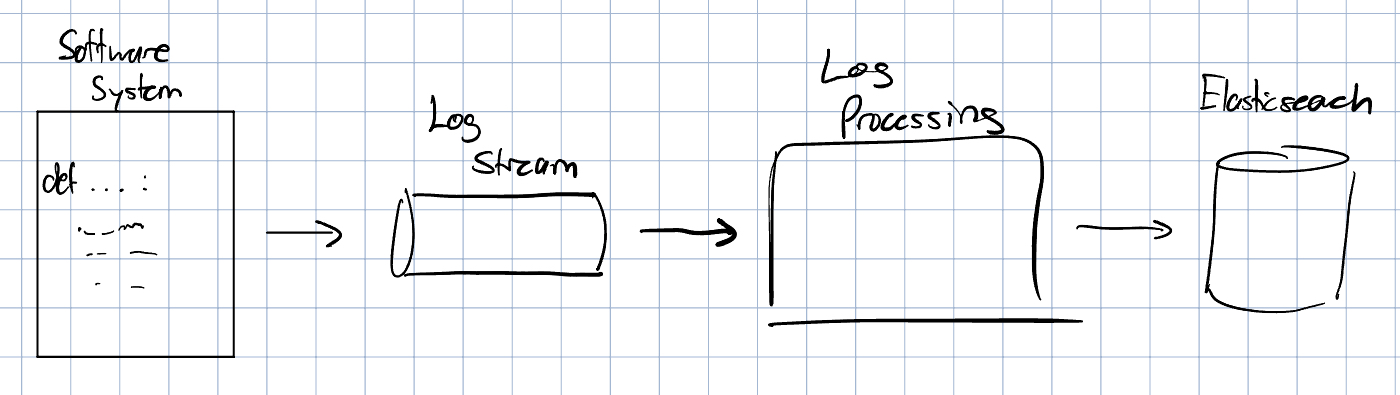

First, it’s important to understand how modern software engineering uses logs. Logs are an essential component in observing how systems work; they contain information useful for understanding where the system went wrong or collecting important performance metrics. Typically, logs are emitted from software applications and collected into a log stream, where processing occurs to make logs easy to search and understand. These processed logs are then dumped in special databases to make log querying easy.

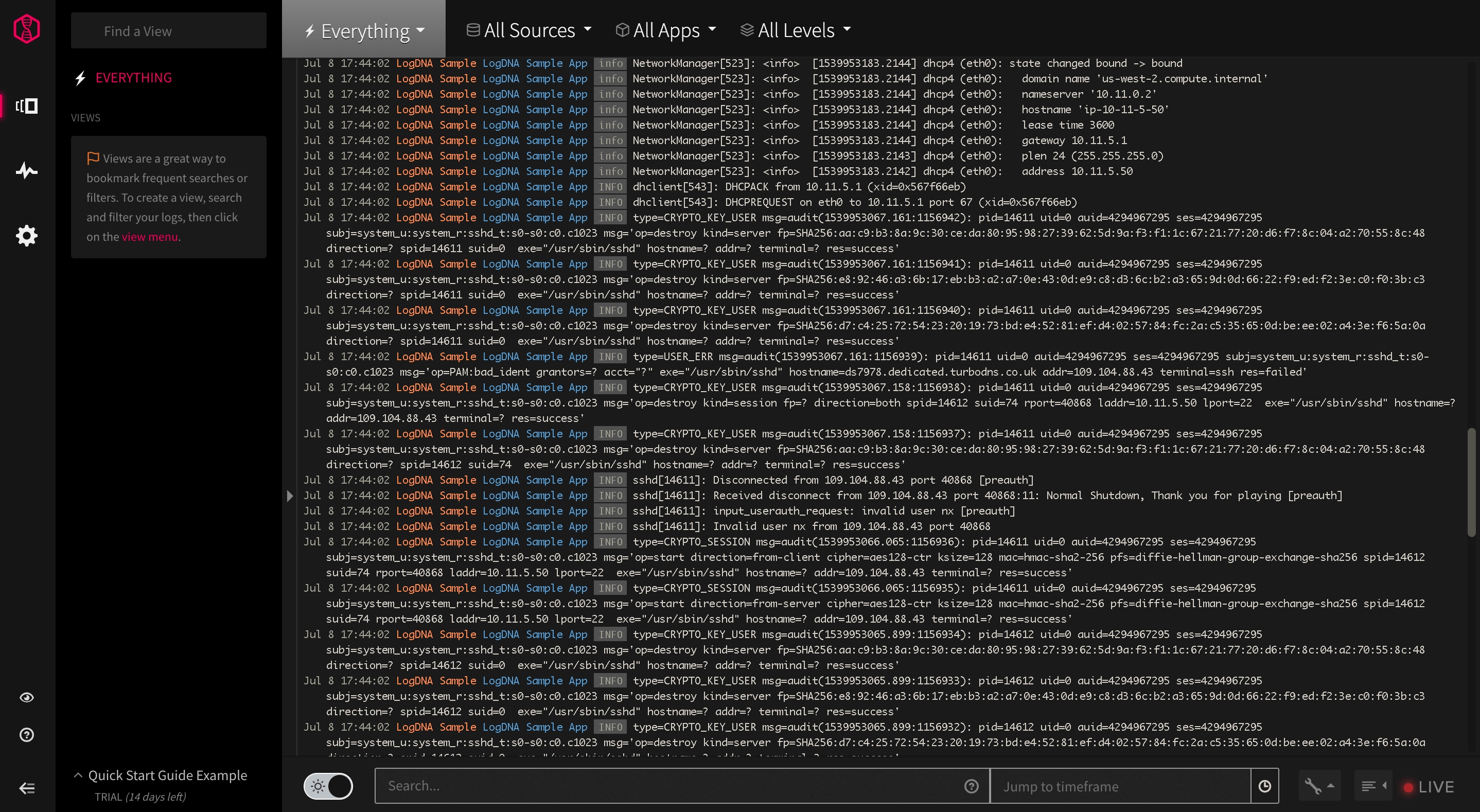

What do logs actually look like? Here’s an example:

As you can tell, logs are just plain strings of raw, dense information. This is why we need to process logs. One part of processing logs is parsing, where we separate out the components of logs into structured components that we can easily search.

To parse logs, we need to understand what parts of our logs change (dynamic) and what parts don’t (static). Many logging systems enable developers to indicate what parts of a log are dynamic and what is not dynamic, but that requires coordination among engineers to ensure that they are using the same variables and logging standards. Automatic parsing is a big interest in the research community.

Currently, parsers used in industry require the usage of regex patterns to extract dynamic and static parts from a log, but this raises a couple of issues:

- Regex is quite difficult to maintain

- If log formats change, then regex patterns need to change

This brings us to the main question the log parsing community is working on: can we parse logs without needing regex? Can we use natural language techniques to do?

(And to the ML bros: ML is a decent idea but it doesn’t work practically in the high-scale environments of log parsing, where logs must be converted within milliseconds. Maybe if technology catches up where inference time can be that quick, it might become a practical approach)

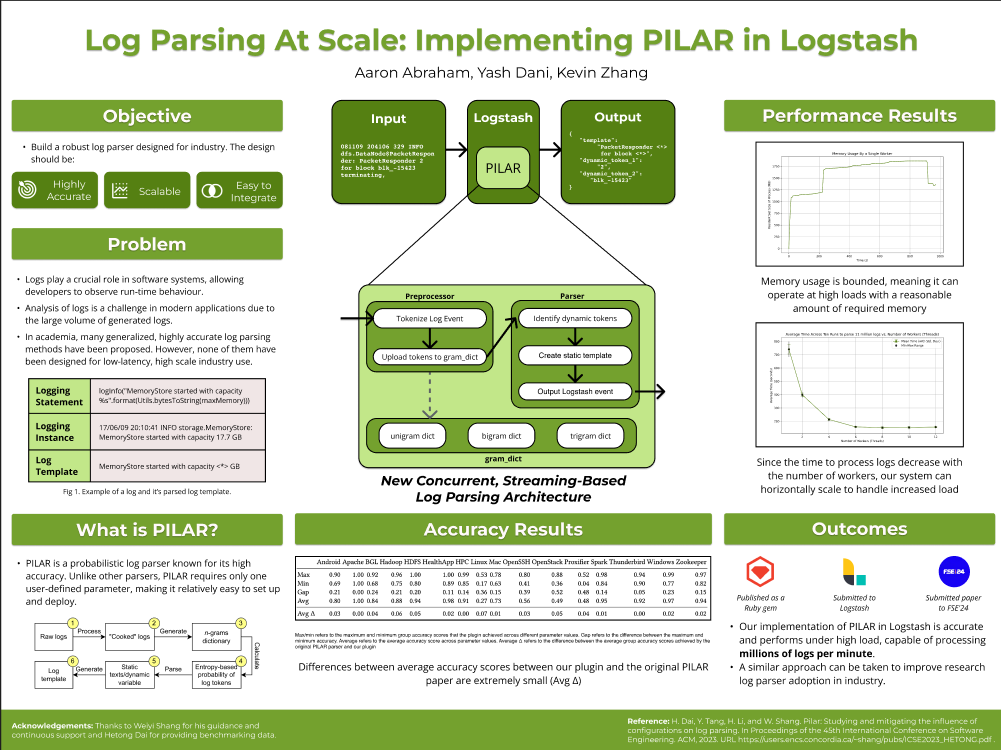

Our professor worked on an algorithm called PILAR that uses basic n-gram processing techniques to identify the static and dynamic parts of a log, but it was a proof-of-concept algorithm that could not be used in a production system. The initial algorithm could not handle millions of log events being thrown at it in a single second, Furthermore, the system could not integrate with popular logging systems and could not handle parsing log streams; it could only parse files of logs.

Our project revamped his initial system into a log parsing plugin that could be used in extremely performant software engineering environments. We made several improvements to his algorithm, including:

- Converted the algorithm into a plugin that could integrated into Logstash, a leading open-source log framework used in many companies

- Re-architected the system to enable stream processing of logs

- Engineered several optimizations, including concurrency and caching, to make PILAR work at lightning speeds.

We finished most of the work in our 4A term while we were on exchange, having weekly calls and doing a bunch of async work. In our 4B term, we did some final touchups and performance benchmarking and finally presented our project at the SE Symposium. You can check out our poster below (made in Figma):

Our professor encouraged us to submit the project to the Foundations of Software Engineering Student Research Competition. We unexpectedly got accepted for our submission and wrote up a paper for a competition, a first for all of us on the team. Our submission can be found here. Feel free to email me if you want the manuscript!

Tips for success on FYDP

FYDP can be an unnecessary stressful burden for many engineering students. Here are some tips to make it a more enjoyable experience:

- Choose a good team: This is absolutely crucial and probably the biggest determinant if you will end up enjoying FYDP. How do you derisk your team selection? You need to work on small projects with them. Fortunately, SE’s FYDP program has an inbuilt method to try out a bunch of different projects with a team. I know a few people that found out that their initial team was not a good fit for their working style. It is much better to find this out early when you have committed deeply to any particular topic.

- Look into research projects: research projects with professors are a great fit for FYDP as they are often well-scoped and are marked quite easily compared to “new product” categories. However, approaching professors to collaborate on a research project is a delicate art. Rather than cold-emailing professors and seeing if they have any available projects, you should try to align your interests with professors and propose topics that are in-line with their current research. This shows a lot more initiative to professors and they are a lot more willing to take your team under their wing.

- Explore before you commit: One great thing about the SE FYDP program is that we have the chance to try out 3 different projects before we begin. If you are an SE student, use this time wisely to explore different ideas and different types of projects.

- Frontload: Personally, my priority in 4B was to enjoy the last term with my friends and spend time with them as much as possible. FYDP can be a detractor from this, so try to do most of your work before 4B so you have your last semester to do whatever your heart wishes

Overall, FYDP was a great cherry on top of the SE experience. I had a great time building this project with my friends and learning more about a field of software engineering that I didn’t know much about. FYDP is an excellent opportunity for students to dive into their interests and marry it with software engineering principles!