Context

During my exchange semester in Spain, I took a course in cryptography. I found it to be the one of the most interesting subjects that I have taken in university as it took math that I learned about it my first year of undergraduate studies in a direction that I didn’t expect. The beauty and simplicity of ciphers and other cryptographic primitives took me by surprise.

I was especially interested in cryptography because I kept running into these concepts during my software engineering internships. HTTPS, OpenSSL, end-to-end encryption,…the list goes on how central cryptography is to our daily lives. A great majority of the network traffic on the Internet today is encrypted, and many of the new messaging apps like Signal and Telegram comfort users by promising them that all information is encrypted at rest and at transit.

After I came back to Calgary from Spain, I came across a very interesting story that shook my core belief that most cryptographic protocols are secure. What if these protocols are engineered in a way such that actors can get access to our plaintext communications easily? What if there’s a backdoor in many of the algorithms that we take granted for today that makes decryption a piece of cake for agencies like the NSA, CSEC and GCHQ? I want to share this gripping tale of math and cyber warfare techniques because it speaks volumes to how vulnerable we are as digital citizens.

A primer on elliptic curves

Before we get into cryptography, let’s first take a look at some maths. The centre to this story is the elliptic curve, which is defined as:

where and are part of some field. A field is simply a set of numbers where addition, subtraction, multiplication and division are well defined and behave just like real numbers and rational numbers. For example, the real numbers is an example of a field.

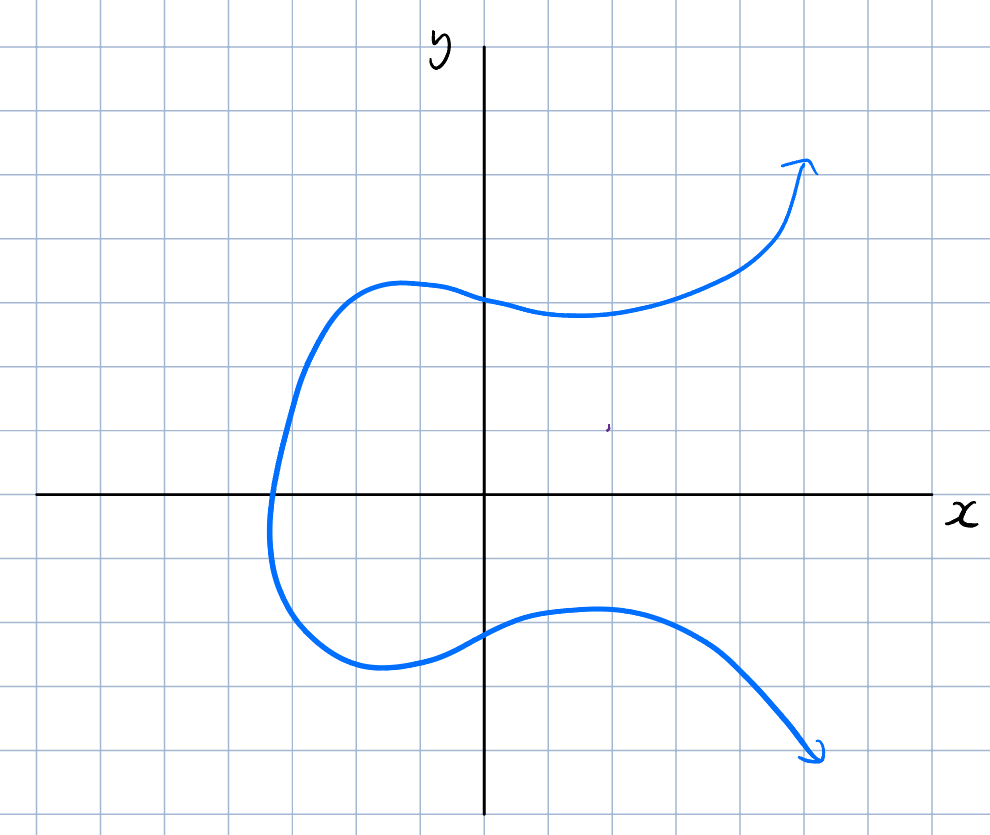

Let’s look at an example of an elliptic curve. From the equation (and not from the following shoddy diagram), note how these curves are symmetric about the -axis:

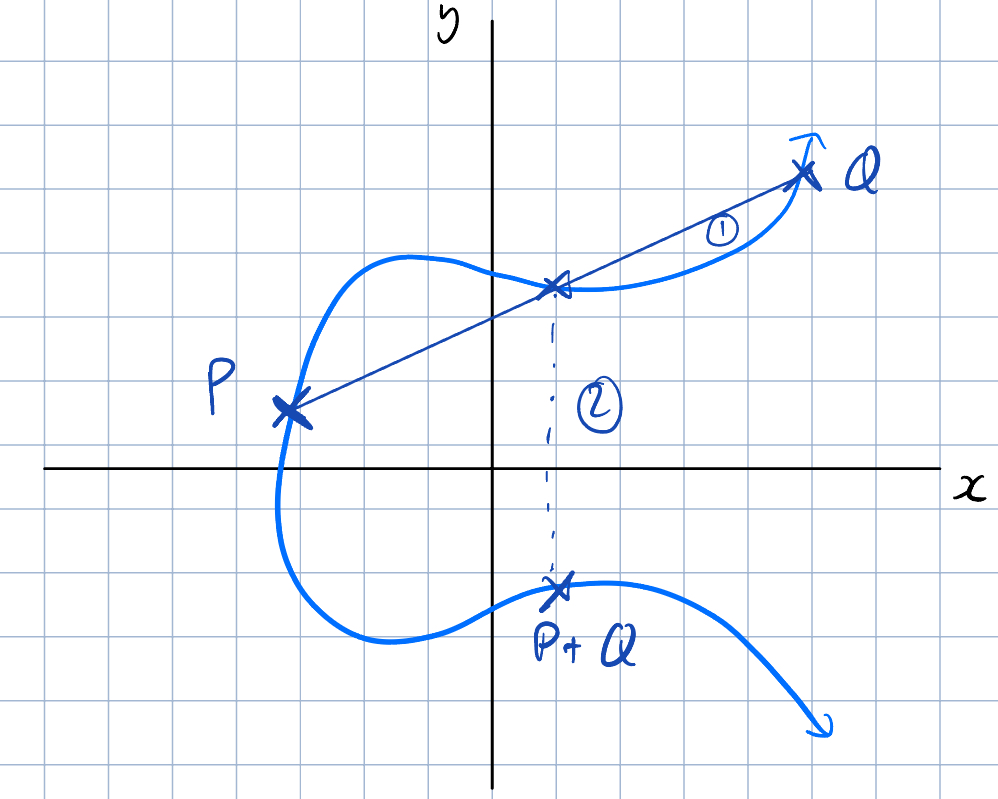

Elliptic curve cryptography relies on the concept of point addition on elliptic curves. Given points and , the point can be derived by following this algorithm:

- Construct a line that connects both points

- Find the point that intersects with the curve and this line

- Draw a perpendicular line from the point of intersection across the -axis. The point of intersection of this perpendicular line and the elliptic curve is the point

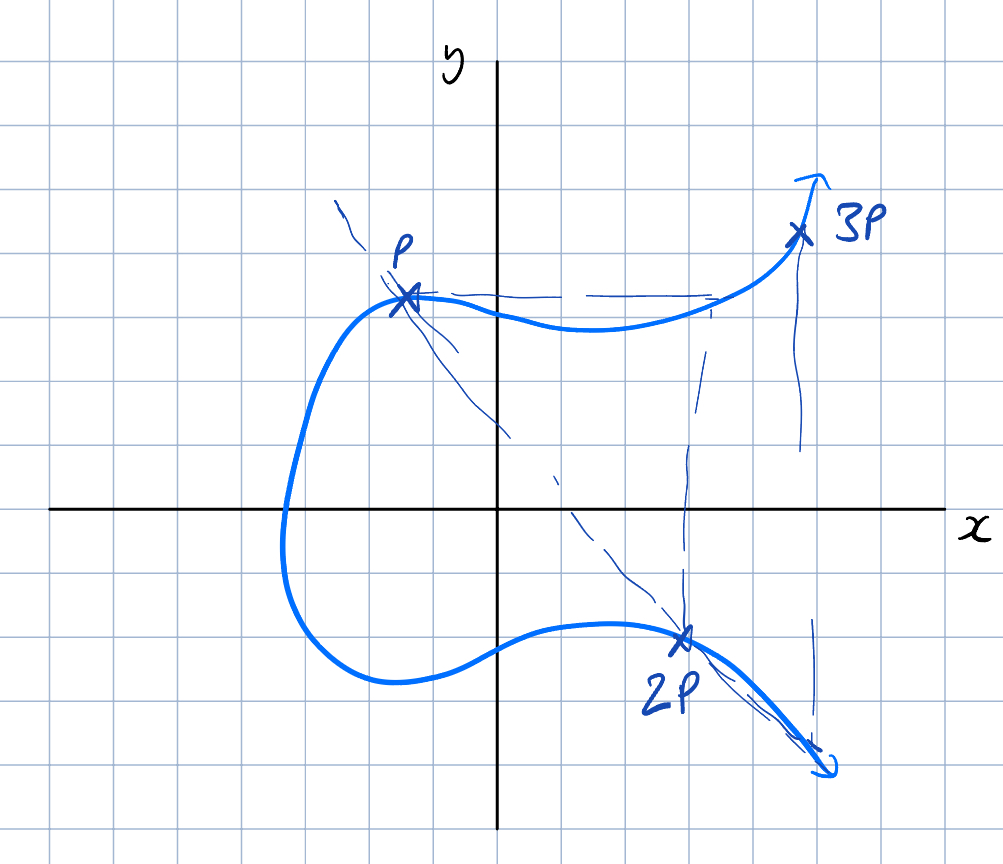

We are specifically interested in repeated point addition. Let’s say we have some point on the curve. To find the point , we take a tangent line to for step 1 in the above algorithm. To find , we can just take a line connecting and for step 1. We can do this over and over again to find the point where is the number of times that we added to itself.

There are two important results from repeated point addition:

- Finding the value of in is a very hard problem if you only know and . It is known as the elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem (ECDLP) and would take a lot of computational resources, unless, of course, you have a quantum computer.

- Points generated from repeated point addition seem quite random when plotted. This is a property that we will use to generate pseudorandom number generators.

A pseudorandom generator using elliptic curves

A problem that computers face is generating random numbers. By definition, there’s no real way of constructing a random generator of numbers, so instead computer scientists opt for functions that mimic randomness, which are known as pseudorandom number generators, or PRNG.

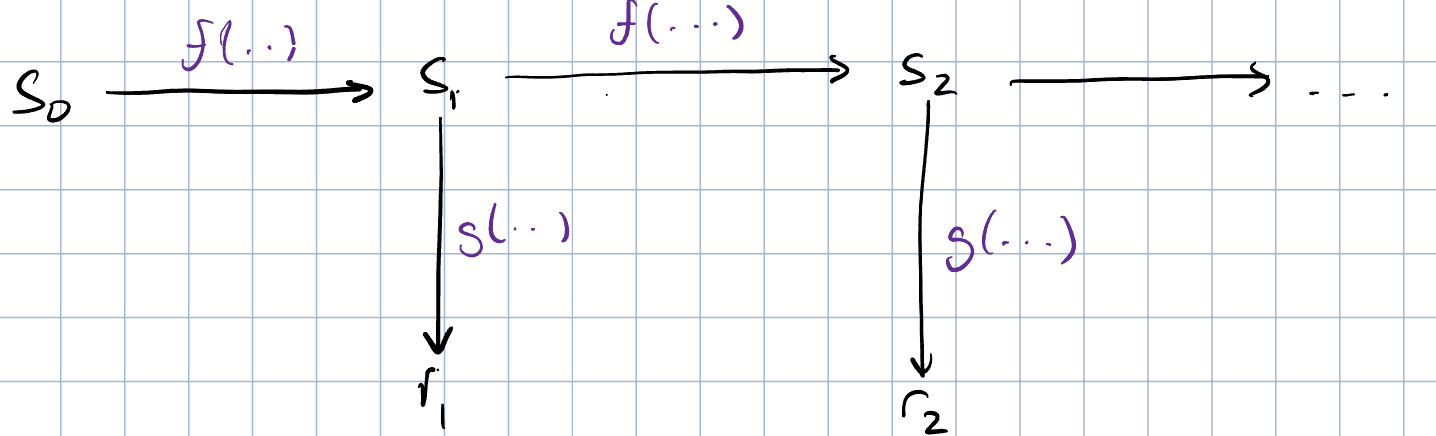

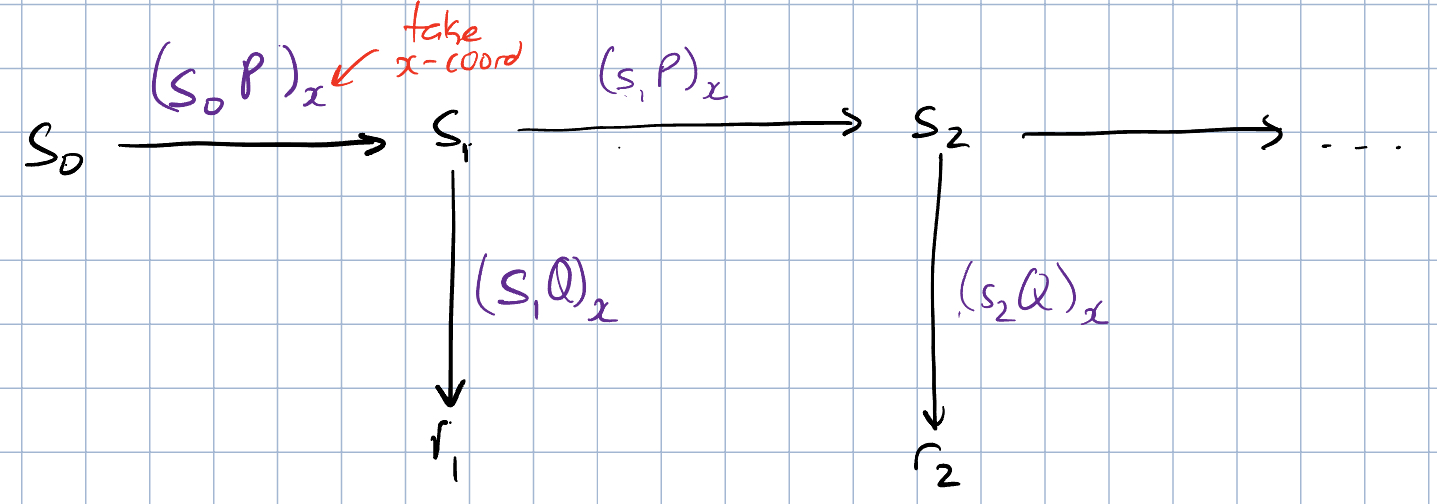

Typically, a PRNG is constructed like so:

We initially start with some seed value that can be taken from any source of entropy (eg. the number of CPU cycles from when our computer started up). This seed is passed through a one-way function to generate the first state . To generate the random number, we calculate where is another one-way function and calculate the next state . We can keep doing this every time a random number is requested. Note that this heavily relies on one-way functions. A one-way function is a function where it’s trivial to calculate but it is very hard to find the inverse of .

Why exactly do we we care so much about using one-way functions? A central tenet in PRNG design is that outputs should not leak any knowledge of internal state. If an attacker can find out the internal state of a PRNG, it’s trivial for them to know the future of the PRNG.

The two properties that we mentioned above with elliptic curves come in great use for PRNGs. If we replace our one-way functions with just repeated point additions on an elliptic curve, we get pseudorandom behaviour and one-way behaviour through ECDLP. This PRNG is known as dual EC DRBG. Here, we have two points and defined on an elliptic curve; these are the parameters for this PRNG. The -coordinate of each point addition is used for the output of the one-way functions.

Why exactly are PRNGs so important for cryptography? Let’s take a step back and talk about a classic scenario. Let’s say Alice wants to send a message to Bob, but is afraid that someone might see her message. The naive solution is for Alice to encrypt the message and calculate where is the encrypted message that Alice can send to Bob and is some encryption algorithm that uses a key . This key is important, because it can also be used by a decryption algorithm to take and transform it back to , which Bob will use. PRNGs are often the source of these keys. This is important: if we crack the PRNG, we can predict the key used in the encryption and decryption algorithms.

The backdoor

Dual EC is not the only PRNG. In fact, there are multiple algorithms out there for PRNG and similarly, multiple algorithms for encryption and decryption. Software developers who are using cryptographic protocols don’t want to read the latest literature in cryptography to figure out the most secure and computationally easy cryptographic algorithm. To solve this problem, the United States government started the National Institute of Standard and Technology (NIST), which publishes standards for use in cryptography and other scientific fields. NIST also has a mandate to ensure that cryptographic standards that it publishes are secure; this makes it easy for software developers to use NIST-published cryptography in their own systems.

In 2004, dual EC DRBG was published by NIST as a recommended PRNG. However, there were a few things that were a little strange with the publication of this PRNG. For one, the parameters for dual EC DRBG seemed to be quite random. Usually, NIST chooses parameters that all cryptographers know, such as the first few digits of pi (these are known as nothing-up-my-sleeve-numbers, or NUMS); the dual EC parameters were not from this list. A more pressing issue was the discovery that dual EC is pretty slow. With these two concerns, cryptographers all but discarded the dual EC approach.

Eventually, cryptographers found out why dual EC parameters for the elliptic curve ( and ) as well as and were chosen; it’s a backdoor to the PRNG! Let’s walk through the simple math behind the backdoor.

Let’s assume that and are related such that as defined in an elliptic curve. Let’s also say that we are able to get the output of a dual EC PRNG as . If we know all of these variables, then we can reconstruct the internal state of the PRNG:

- We know

- We can calculate , which is the internal state of the PRNG

Furthermore, this value of is hard to calculate since it is protected by ECDLP. If someone knows , then this PRNG is not secure at all, even if the initial state is chosen at random.

In 2013, some shocking news came out from Edward Snowden and resulting investigations: the NSA purposefully planted this backdoor into the NIST standards. Furthermore, dozens of commercial cryptography libraries used dual EC DRBG even though it was proven to be vulnerable and slow.

What was quite shocking about these allegations was the level of involvement between the NSA and NIST. NIST is in fact required by law to consult with the NSA when establishing cryptographic standards, nominally for ensuring cryptographic standards are secure. However, in this scenario, there was a much more sinister relationship between the two: the NSA purposefully pushed NIST to publish dual EC DRBG with these parameters because the NSA knew . When NIST published these standards, the NSA started their next phase of infiltration: get companies to use dual EC DRBG. In fact, an investigation surfaced that the NSA paid RSA Security $10 million to use dual EC as the default PRNG in their algorithms. For companies that used open-source OpenSSL for cryptographic protocols, the NSA simply contributed to OpenSSL to use dual EC PRNG.

Now there is an easy way to bypass this backdoor: choose your own and . However, ensuring that there is no relationship between the two parameters is not a trivial task. Furthermore, NIST recommended not to choose these parameters. This guidance is also likely to be from the NSA.

Takeaways

When I first learned about this story, I was shocked. NIST is known throughout the world for publishing cryptography standards and I had thought it would be governed by a third-party board. However, learning about this level of cooperation between the NSA and NIST makes it very difficult to trust many of the published cryptography standards from NIST. Who knows how many other algorithms and primitives are compromised by the NSA in a manner similar to dual EC?

The multi-pronged attack that the NSA executed is a classic supply chain attack. Supply chain attacks inject vulnerabilities into different parts of the software stack, such as open source libraries, and can target even the most basic primitives that our software relies on. In this case, the PRNG cryptography primitives were attacked. Supply chain attacks are particularly concerning; even if you do everything in your power to ensure your software is secure, one leaky library can lead to disastrous consequences. Supply chain attacks are becoming more common as it is very easy to implement; examples of software supply chain attacks include:

- Infecting open-source library updates with malicious code

- Undermine codesiging: when libraries are downloaded, a hash of the library is often compared with the published hash to ensure integrity. Undermining codesigning can allow malformed libraries to be installed

- Prevent communication with 3rd-party library repositories so that users don’t update software

Cyber warfare is becoming more ingenious and our responsibilities as software engineers means that we should try our best to stay abreast of these changing attack vectors; our clients and users are ultimately the ones that will pay the cost. Supply chain attacks are something we will all likely encounter in our careers; we should be ready to fight back and proactively close these vulnerabilities when they do arise.